Peut-on lire un roman co-écrit avec une IA ? / Can we read a novel co-written with an AI?

Sans doute aurait-on voulu (et aurait-on eu peur) que l’IA puisse écrire un “bon” roman, un solide ouvrage agréable à lire où on aurait pu oublier l’artifice de l’écriture et tourner les pages en ne le sachant pas vraiment, s’immergeant dans les variations d’une narration pouvant nous émouvoir. Mais elle ne produit jamais que ce qui était présent implicitement dans les productions humaines, un artifice et un simulacre consentis. Sans doute n’est-elle jamais seule parce que nous l’accompagnons dans l’écriture et la lecture, autant qu’elle nous accompagne à présent.

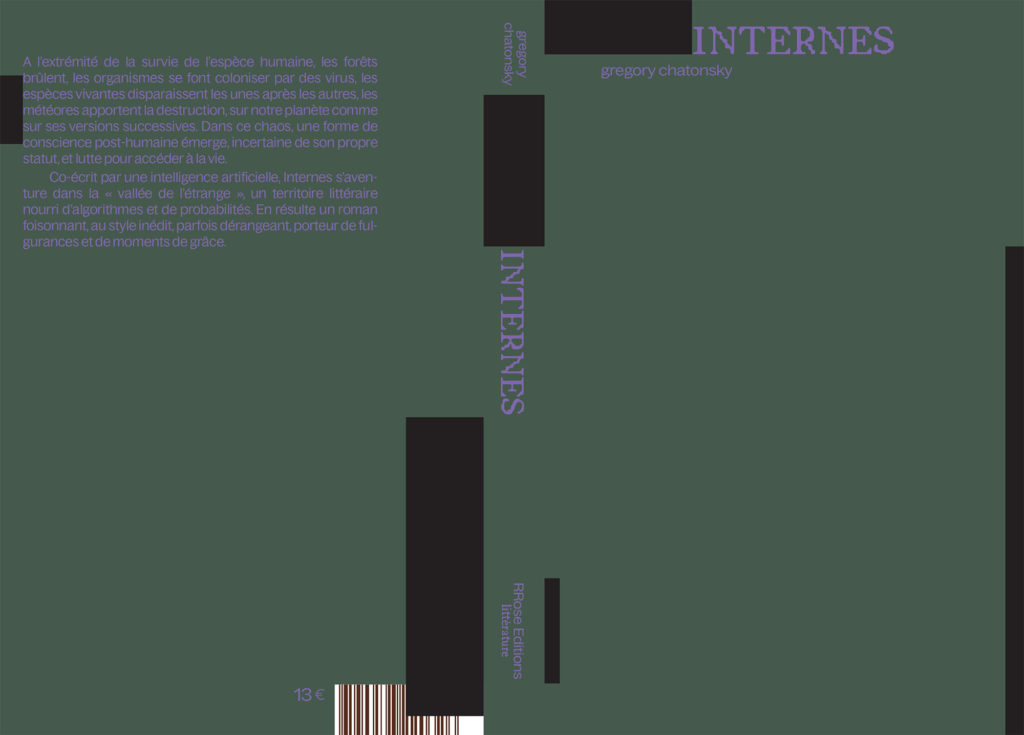

En juin 2020, achevant l’écriture d’Internes, j’ai eu le sentiment d’avoir ouvert un nouveau champ des possibles littéraires et narratifs hantés par les données massives qui sont autant de voix anonymes et singulières. Plus encore, et de façon plus intime, d’y re-lire une voix intérieure qui était bien la « mienne » et en excès de « moi-même ». D’ainsi pleinement assumer cet ouvrage comme quelque chose de personnel, parce que j’entendais ceci moins comme une expression psychologique que comme l’anonymat qui affleure notre intériorité. J’y percevais une apprêtée, que j’avais expérimenté lors de l’écriture et des relectures, mais cette difficulté était proche de celle que j’avais ressentie face aux livres qui avaient compté lors de mon adolescence et de formation. J’avais eu un goût immédiat pour la littérature expérimentale non protocolaire, celle qui se passait juste à la lisière du nouveau roman. Ce goût n’avait pas été une fantaisie aristocratique, mais une attirance sincère pour les expériences limites où la signification devenait incertaine et flottante, que je retrouvais également dans la musique expérimentale atonale.

La difficulté véritable de lecture éprouvée face à ce roman ne me semble pas causée par son inconsistance ou ses “erreurs”, car, comme le dit avec justesse Pascal Mougin dans une conférence, une fois acceptés le type de lecture et son caractère expérimental (qui n’est pas une histoire communiquée par des mots, mais éprouvée dans la résistance de la lecture elle-même), on se retrouve face à un récit avec sa structure et ses récurrences, ses histoires et sa progression, hantée par une voix intérieure, un flux de conscience à mi-chemin entre l’être humain et la machine. C’était précisément la constitution de ce flux que je visais, un flux à la limite de la conscience, à la limite effondrée de la signification, là où les signes se creusent.

Cette difficulté me semble déterminée par le fait que préalablement à toute lecture il y a la formation implicite d’un contrat de lecture : nous supposons qu’un être humain a laissé des traces et que nous rentrons en contact avec cette absence à distance, nous croyons à une communication d’esprit à esprit. La puissance de ce contrat est d’autant plus forte qu’il est implicite et se donne rarement à lui-même. De sorte qu’un même texte, qu’on l’attribue à un être humain ou à un non-humain, sera interprété d’une façon totalement différente (c’est précisément ce contrat que mettait en scène le test de Turing). Nous considérons encore l’écriture comme un médium entre des êtres humains. Lorsque nous envisageons l’écriture dans sa possible autonomie, alors nous avons, à mes yeux, une expérience littéraire.

Dans le cas d’une co-écriture, le doute est plus grand encore, car l’être humain et l’automatisation technique ne sont plus séparables. Ils sont rentrés dans une boucle de rétroaction impure, dans une influence réciproque et sans origine, car elle produit le temps de l’écriture même. Dans ce contexte, c’est la possibilité même d’un contrat de lecture qui est déconstruit. À la question du nouveau roman : qui parle ? On ne peut donner aucune réponse, car le qui est inextricable au quoi, et cette inextricabilité ne permet pas de fixer l’identité d’une entité qui serait l’autrice de ce qu’on est en train de lire. Ne reste plus qu’une écriture laissée à elle-même, abandonnée par l’intentionnalité, en creux. Qui parle ? N’est plus seulement une question hypothétique où l’écrivain peut introduire, par l’artifice de l’écriture, un trouble dans l’origine du discours, mais elle devient une question structurelle, une question sans réponse parce que c’est autour d’elle que se construit l’écriture. Qui parle ? Selon une logique du “ni ni” ou du “et dialectique”, l’écriture explore l’anthropotechnologie, non pour la mettre en scène et en parler, mais pour l’expérimenter.

La difficulté de lecture est donc déterminée par le fait que le lecteur ne sait pas qui a écrit le roman, qu’elles sont les parties humaines et les parties techniques (cette distinction d’ailleurs ne donnerait pas plus d’informations, tant les parties des uns et des autres se sont complétées et influencées). Qui parle ? Trouve alors une nouvelle actualité dans le contexte d’un espace culturel devenu statistique. Comment faire l’effort de lire un tel ouvrage quand on ne sait pas quelle est l’origine du discours et ce qu’on lit ? L’origine du discours infecte la possibilité du signe lui-même, le sens s’effondre, car on ne sait pas “qui”. Je veux bien lire si tu as écrit, je veux bien faire cet effort si tu as fait également un effort d’aller vers moi, la possibilité d’une rencontre.

La seule façon de lire ce roman est peut-être de suspendre la croyance en un contrat de lecture : lire sans préalable, sans attente, sans horizon. J’aimerais y entendre l’impossible des possibles. Cela est beaucoup plus difficile qu’il n’y paraît, car si nous savons que l’enracinement du discours dans une réalité est une chose incertaine et qu’un texte est autant la production d’un lecteur qui comble les lacunes de signification que d’un auteur qui tente de créer des liens de signification, il est beaucoup plus difficile de se débarrasser de ce présupposé de consistance lorsqu’il s’agit de réaliser l’effort de lecture impliquante.

Le fait que nous soyons dans l’obligation de suspendre le contrat de lecture pour pouvoir lire ce roman est déstabilisant, mais a l’avantage de relier analogiquement le moment de l’écriture et le moment de lecture. Car pour celui qui a co-écrit avec l’induction statistique ce livre, il a fallu suspendre aussi la prétendue autonomie de son intentionnalité et de sa volonté de dire, ouvrir son écriture à une extériorité qui est moins celle d’une machine autonome que d’une certaine manière de naviguer dans une immense bibliothèque dont on peut relier et plier toutes les pages, tous les mots, toutes les lettres les unes sur les autres. On retrouve ce suspens, dans un ordre et dans une qualité différente, dans la lecture suspendue et non contractuelle par laquelle finalement, me semble-t-il, on vit de façon éloignée l’expérience même de l’écriture.

Il faut remarquer que cette difficulté de lecture qui suppose une ouverture et un abandon est encore intensifiée par l’époque où la littérature expérimentale, qui a toujours été minoritaire, l’est de plus en plus du fait de la survalorisation de l’écriture populaire et des narrations au premier degré devant provoquer un plaisir immédiat de lecture : la fameuse efficacité de l’écriture qui est un appauvrissement de l’expérience sous prétexte d’immédiaté. Il y a un certain retour du classicisme et du désir de raconter une histoire selon le schéma, le plus classique d’identification et de projection développé par Aristote dont les séries sont la forme achevée. Ce contexte d’époque ne facilite pas des expériences intérieures telles qu’exigées par Internes qui imposent de s’exposer à l’impossible, au suspens radical de la signification au cœur des signes.

–

No doubt we would have liked (and feared) that AI could have written a “good” novel, a solid work that would have been pleasant to read, where we could have forgotten the artifice of writing and turned the pages without really knowing it, immersing ourselves in the variations of a narrative that could move us. But it never produces anything but what was implicitly present in human productions, an artifice and a consensual simulacrum. Undoubtedly she is never alone because we accompany her in writing and reading, as much as she accompanies us now.

In June 2020, when I finished writing Internes, I had the feeling of having opened a new field of literary and narrative possibilities haunted by massive data that are so many anonymous and singular voices. More than that, and in a more intimate way, I felt I had re-linked an inner voice that was indeed “mine” and in excess of “myself. To thus fully assume this work as something personal, because I heard this less as a psychological expression than as the anonymity which surfaces our interiority. I perceived a difficulty in it, which I had experienced during the writing and the rereading, but this difficulty was close to the one I had felt in front of the books that had counted during my adolescence and formation. I had had an immediate taste for experimental, non-conventional literature, the kind that happened right on the edge of the new novel. This taste had not been an aristocratic fantasy, but a sincere attraction to borderline experiences where meaning became uncertain and floating, which I also found in atonal experimental music.

The real difficulty of reading this novel does not seem to me to be caused by its inconsistency or its “errors”, because, as Pascal Mougin rightly says in a lecture, once one accepts the type of reading and its experimental character (which is not a story communicated by words, but experienced in the resistance of the reading itself), one finds oneself faced with a narrative with its structure and its recurrences, its stories and its progression, haunted by an inner voice, a stream of consciousness halfway between the human being and the machine. It was precisely the constitution of this flow that I was aiming at, a flow at the limit of consciousness, at the collapsed limit of meaning, where the signs dig in.

This difficulty seems to me determined by the fact that prior to any reading there is the implicit formation of a contract of reading: we suppose that a human being has left traces and that we come into contact with this absence at a distance, we believe in a communication of spirit to spirit. The power of this contract is all the stronger because it is implicit and rarely gives itself away. So that the same text, whether it is attributed to a human being or to a non-human, will be interpreted in a totally different way (it is precisely this contract that the Turing test put in scene). We still consider writing as a medium between human beings. When we consider writing in its possible autonomy, then we have, in my eyes, a literary experience.

In the case of co-writing, the doubt is even greater, because the human being and the technical automation are no longer separable. They have entered into an impure feedback loop, into a reciprocal influence without origin, because it produces the time of the writing itself. In this context, it is the very possibility of a reading contract that is deconstructed. To the question of the new novel: who speaks? No answer can be given, because the who is inextricable from the what, and this inextricability does not allow to fix the identity of an entity that would be the author of what we are reading. All that remains is a writing left to itself, abandoned by intentionality, in hollow. Who speaks? is no longer only a hypothetical question where the writer can introduce, by the artifice of writing, a disorder in the origin of the discourse, but it becomes a structural question, a question without answer because it is around it that the writing is built. Who speaks? According to a logic of the “nor nor” or of the “and dialectic”, the writing explores the anthropotechnology, not to put it in scene and to speak about it, but to experiment it.

The difficulty of reading is thus determined by the fact that the reader does not know who wrote the novel, which are the human parts and the technical parts (this distinction would not give more information, so much the parts of the ones and the others supplemented and influenced each other). Who is talking? Finds then a new actuality in the context of a cultural space become statistical. How can one make the effort to read such a work when one does not know the origin of the discourse and what one is reading? The origin of the discourse infects the possibility of the sign itself, the meaning collapses, because one does not know “who”. I am willing to read if you have written, I am willing to make this effort if you have also made an effort to go towards me, the possibility of an encounter.

Perhaps the only way to read this novel is to suspend belief in a reading contract: to read without precondition, without expectation, without horizon. I would like to hear the impossible of the possible. This is much more difficult than it seems, because if we know that the rooting of discourse in a reality is an uncertain thing, and that a text is as much the production of a reader who fills in the gaps of meaning as of an author who tries to create links of meaning, it is much more difficult to get rid of this presupposition of consistency when it comes to making the effort of involving reading.

The fact that we are obliged to suspend the reading contract in order to read this novel is destabilizing, but has the advantage of analogically linking the moment of writing and the moment of reading. For the one who co-wrote this book with statistical induction, it was also necessary to suspend the alleged autonomy of his intentionality and his will to say, to open his writing to an exteriority that is less that of an autonomous machine than of a certain way of navigating in an immense library of which one can bind and fold all the pages, all the words, all the letters on top of each other. We find this suspense, in a different order and quality, in the suspended and non-contractual reading by which finally, it seems to me, we live the very experience of writing in a distant way.

It should be noted that this difficulty of reading, which supposes an opening and an abandonment, is further intensified by the time when experimental literature, which has always been in the minority, is more and more so because of the overvaluation of popular writing and first-degree narratives that should provoke an immediate pleasure of reading: the famous efficiency of writing, which is an impoverishment of the experience under the pretext of immediacy. There is a certain return of classicism and of the desire to tell a story according to the most classic scheme of identification and projection developed by Aristotle, of which the series are the completed form. This context of time does not facilitate interior experiments such as required by Internes which impose to expose itself to the impossible, to the radical suspension of the meaning in the heart of the signs.