Le disréalisme inductif / Inductive Disrealism

L’industrialisation des images et la circulation planétaire de celles-ci ont entraîné une profonde modification au fil du XXe siècle de la valuation des images. Il y a plus d’images que ce que nous pouvons voir et cet univers est transfini parce qu’il grandit beaucoup plus rapidement que notre faculté à le parcourir individuellement et collectivement. Cette surproduction des images est inséparable de la surproduction industrielle et ses conséquences matérielles.

La modernité, du cubisme au pop art et au-delà, a porté son regard sur cette évolution des images, sur leur grand nombre excessif pour nos capacités perceptives jusqu’aux déchets en tentant, par exemple, d’en extirper certaines du flot interrompu afin, par un tel choix, de leur redonner une valeur esthétique. Par exemple, l’artiste sélectionne une image et la traite avec des techniques anachroniques sans rapport avec sa valeur. C’est son faire d’artiste qui redonne une valeur à l’image. Or cette manière de faire n’a produit finalement qu’une autre fétichisation de l’image qui a été remise en circuit dans le capital et la spéculation. Elle est devenue une image parmi d’autres, circulant et reprise à son tour. Ainsi le recyclage des images médiatiques et des stratégies du popart dans le street art sans aucune capacité de perturbation en est le symptôme.

L’ironie dans l’art contemporain a mis en scène la critique et cette dernière a participé à la quantité qui nous déborde en ne gardant, comme événement, que la fétichisation de l’art, activité que l’on préserve on ne sait plus trop pourquoi. L’ironie participe du capitalisme, il est le clin d’œil de sa réflexivité : « on ne nous y prendra pas » et « on sait ce qu’il en est ».

Or l’immense quantité des images, qui a aujourd’hui pris la forme du big data sur le Web, constitue non seulement une nouvelle ère de l’historicité (que feront les historiens futurs de notre époque hypermnésique ?), mais est aussi au fondement fonctionnel de l’induction statistique de l’IA qui s’en nourrit.

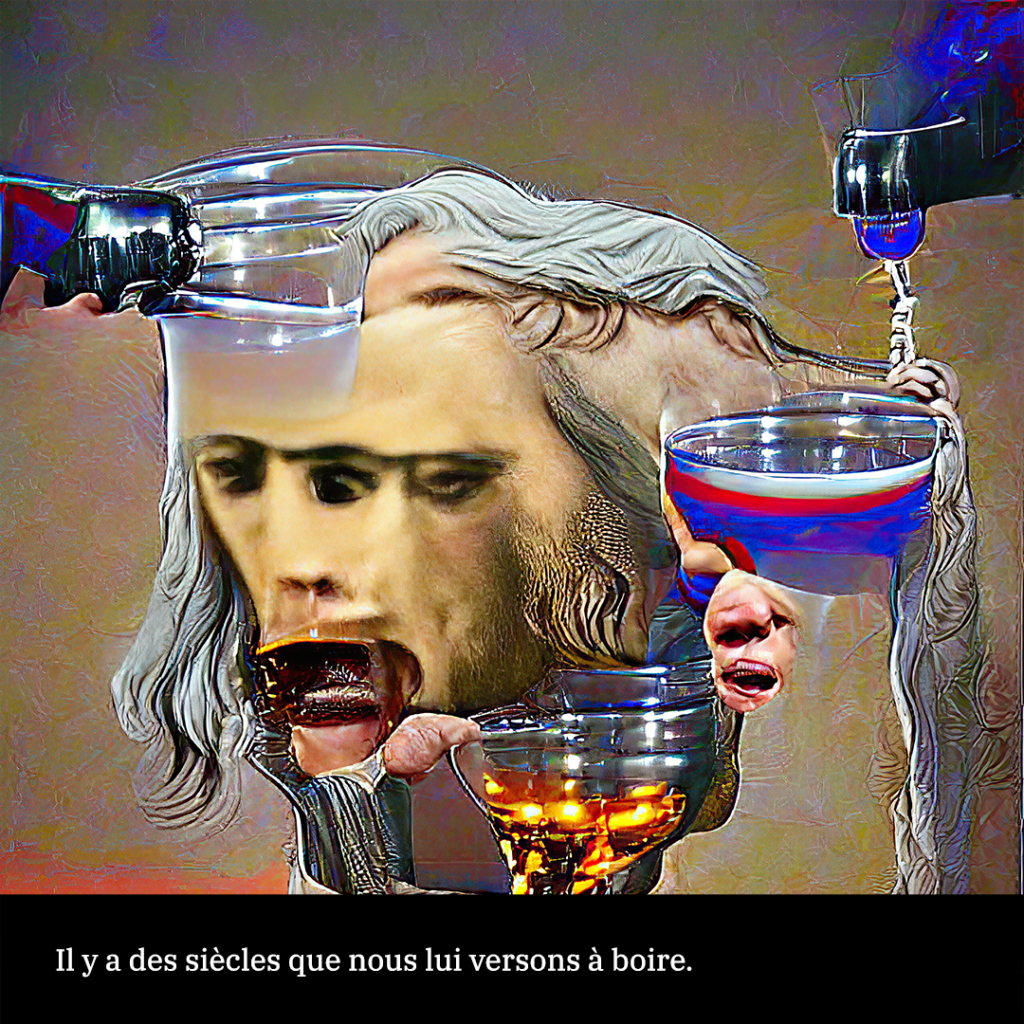

Celle-ci produit un nouveau type d’images et par là même une nouvelle forme de réalisme qui n’est plus strictement photographique, qui en était la forme dominante depuis la révolution industrielle en prétendant à un accès direct, à une empreinte, à l’ontologie par la lumière, mais qui utilise la photographie pour en faire une synthèse statistique. L’IA produit une ressemblance étrange, surréaliste, psychédélique, hallucinatoire, elle nous fait entrer dans un rêve emboîté dans un rêve, le rêve humain de la machine observée par les humains selon la boucle d’une auto-interprétation qui diffère toujours un peu plus son référent. Son caractère kitsch consiste en une circulation des clichés, des biais, des images déjà en circulation. Ces images ont un air de famille avec la visualité en son entier. Ce sont des images d’images.

La ressemblance produite par l’IA n’est compréhensible que perçu par nous, qu’en relation avec nous. Elle n’est pas la production d’une machine autonome ou d’un être humain autonome, mais d’une inextricable relation entre les deux, car elle est la genèse mutuelle de chacun. Elle est une tonalité réaliste, comme on parle de Stimmung, une certaine atmosphère de réalité. Lorsque nous regardons une image produite par une IA, nous percevons bien une forme de réalisme, mais il ne se réfère plus à l’empreinte d’une réalité extérieure, il est la synthèse de données culturelles et mémorielles. L’IA travaille le patrimoine culturel de part en part : le réalisme est le déjà-vu et celui-ci, malgré ce qu’on pourrait croire, n’est pas sans étrangeté, sans surprise, sans défaillance et hésitation.

On peut penser que ce nouveau réalisme inductif est non seulement à la hauteur ou à la mesure des données démesurées du Web de par leur caractère synthétique, mais qu’il permet de surcroît de sortir enfin des contradictions du pop art et de ce qui a suivi, consistant en une fétichisation des images (on en prend une dans le flux faisant de la décision humaine le souverain) ou en un commentaire herméneutique (on prend un objet culturel, un film, et on le rejoue, on le réinterprète, etc. la décision humaine est encore souveraine).

Avec le réalisme inductif de l’intelligence artificielle, il ne s’agit pas de déplacer ces mécanismes dans les machines, mais, plus précisément, dans la relation anthropotechnologique, rendant l’un et l’autre dépendant et par cette réciprocité s’empêchant toute hiérarchisation. Le monde ne se répartit pas entre humains et non-humains, mais selon une ligne de crête entre les deux. Ce réalisme est une manière prometteuse d’absorber, de métaboliser et finalement d’hériter de l’explosion du nombre d’images en circulation qui sont autant de mémoires stockées sur des machines qu’il faut refroidir et qui, au sens propre, brûle la planète et en change l’atmosphère.

The industrialization of the images and the planetary circulation of those have brought a deep modification in the course of the XXth century of the valuation of the images. There are more images than we can see and this universe is transfinite because it grows much faster than our ability to go through it individually and collectively.

Modernity, from cubism to pop art and beyond, has looked at this evolution of images, at their great number, excessive for our perceptive capacities, up to the waste by trying, for example, to extract some of them from the interrupted flow in order, by such a choice, to give them an aesthetic value. For example, the artist selects an image and treats it with anachronistic techniques that have no relation to its value. It is its making of artist who gives a value to the image. But this way of doing has finally produced only another fetishization of the image that has been put back into the circuit of capital and speculation. It has become an image among others, circulating and taken up in its turn. Thus the recycling of the media images and the strategies of the popart in the street art without any capacity of disruption is the symptom of it.

The irony in the contemporary art has put in scene the criticism and this last one has participated in the quantity that overflows us by keeping, as event, only the fetishization of the art, activity that we preserve we don’t know too much more why. The irony participates of the capitalism, it is the wink of its reflexivity: “one will not take us there” and “one knows what it is”.

Now the immense quantity of images, which today has taken the form of big data on the Web, constitutes not only a new era of historicity (what will future historians do with our hypermnesic era?), but is also the functional foundation of the statistical induction of AI that feeds on it.

The latter produces a new type of images and thus a new form of realism that is no longer strictly photographic, which was the dominant form since the industrial revolution, claiming a direct access, an imprint, to ontology through light, but which uses photography to make a statistical synthesis. The AI produces a strange resemblance, surreal, psychedelic, hallucinatory, it makes us enter a dream nested in a dream, the human dream of the machine observed by humans according to the loop of a self-interpretation that always differs a little more its referent. Its kitsch character consists in a circulation of clichés, biases, images already in circulation. These images have a family resemblance with visuality as a whole. They are images of images.

The resemblance produced by the AI is understandable only perceived by us, only in relation with us. It is not the production of an autonomous machine or of an autonomous human being, but of an inextricable relation between the two, because it is the mutual genesis of each one. It is a realistic tone, as we speak of Stimmung, a certain atmosphere of reality. When we look at an image produced by an AI, we perceive well a form of realism, but it does not refer any more to the print of an external reality, it is the synthesis of cultural and memorial data. The AI works the cultural heritage from side to side: the realism is the déjà-vu and this one, in spite of what we could believe, is not without strangeness, without surprise, without failure and hesitation.

One can think that this new inductive realism is not only to the height or to the measure of the disproportionate data of the Web by their synthetic character, but that it allows moreover to leave finally the contradictions of the pop art and what followed, consisting in a fetishization of the images (one takes one in the flow making of the human decision the sovereign one) or in a hermeneutic addition (one takes a cultural object, a film, and one replayed it, one reinterprets it, etc. the human decision is still sovereign).

With the inductive realism of artificial intelligence, it is not a question of displacing these mechanisms in the machines, but, more precisely, in the anthropotechnological relation, making the one and the other dependent and by this reciprocity preventing itself any hierarchization. The world is not divided between humans and non-humans, but along a ridge between the two. This realism is a promising way of absorbing, metabolizing and finally inheriting the explosion of the number of images in circulation, which are so many memories stored on machines that need to be cooled and which, in the literal sense, burn the planet and change its climate.