The déjà-vu as a medium of artificial imagination

La révolution industrielle a été le moment d’une augmentation sans précédent de l’extraction et de la transformation des matériaux, transformation nommée objets. Cette accélération a constitué une transformation libidinale d’importance dans la mesure où le désir fut relié au rythme d’acquisition de ces objets jusqu’au point d’être constitutif du sentiment même d’existence.

La conséquence de ce processus de transformation matérielle et libidinale fut le sentiment d’un déjà-vu permanent. Lorsque nous consommions un objet culturel, nous avions le plus souvent le sentiment de l’avoir déjà vu des centaines de fois avant. Cette impression de clôture de l’espace culturel porta le nom de post-modernisme : nous ne pouvions plus que citer.

Toute une génération s’est sentie porteuse de la nécessité de sortir de cette impasse par exemple en faisant appel à d’autres cultures ou en cherchant à développer des utopies spéculatives. La réalité produite par la production industrielle étant saturée d’avance, il fallait lui imposer une extériorité pour que quelque chose puisse s’ouvrir et que le possible puisse reste possible.

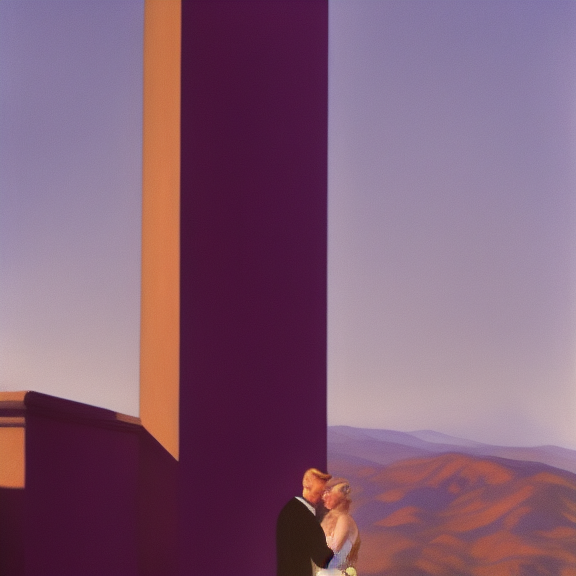

Si l’on peut s’interroger sur l’efficacité de telles extériorité, on doit remarquer que le sentiment de déjà-vu est au cœur de l’espace latent de l’imagination artificielle, car celle-ci en tant quelle est la mise en statistique de millions de documents, est constitutive d’une culture commune ou plutôt d’une calculabilité commune. Une image produite par un réseau de neurones n’a jamais existé, mais a toujours déjà été vue (rendant indépendante la vision de l’image d’un point de vue anthropologique et pas seulement comme machine de vision), car elle est fondée sur les statistiques de millions de documents et elle en est une moyenne qui n’est plus seulement conceptuel mais qui pour la première fois fait image. De sorte que l’impasse dans laquelle nous mettait le sentiment de déjà-vu culturel devient pour ainsi dire un médium. Il ne s’agit plus seulement comme avec le pop art d’extirper du flux médiatique quelques icônes ou comme dans les années 90 et 2000, avec la postproduction des objets culturels de reprendre la figure du DJ capable de remixer quelque chose de déjà d’existant pour en donner une nouvelle version et une nouvelle perception. Il s’agit de se fonder de part en part sur ce qu’il y a déjà existé et on y introduisant du bruit d’y incorporer une légère différence, qu’il faudrait plutôt nommer vibration, qui permet de créer un ensemble métastable entre le reconnaissable répétitif et l’étrangeté d’une possible nouveauté.

Le paradoxe c’est que l’espace latent de l’imagination artificielle est capable de produire la plus grande répétition du déjà-vu comme la plus étrange des différences de la ressemblance. Avec lui on peut répéter à l’identique certains lieux communs visuels de notre époque ou de la manière dont notre époque imagine des époques passées, ou on peut plier et métamorphoser certains de ces espaces pour créer des monstres qui s’ils sont bien fondés sur ce qui a déjà existé, met en présence des formes inattendues. La différence entre ces deux types de déjà-vu est rendue possible par un autre espace latent culturel qui est porté par la personne qui utilise et manie l’imagination artificielle et qui sait ou qui ne sait pas articuler l’intériorité de son espace latent culturel et historique à l’espace latent statistique du réseau de neurones récursif.

Par la même nous sortons bel et bien de l’époque du post-modernisme, à supposer qu’on puisse considérer celui-ci dans la sérialité d’une époque, pour rentrer dans un autre moment qu’on pourrait nommer le disréalisme et qui consiste à naviguer et se perdre dans un espace latent si grand qu’il est impossible d’en avoir une représentation complète et qu’il est seulement possible de s’y déplacer et de trouver certains sous-espaces qui ont ont quelques intérêts et qui savent maintenir un équilibre entre le reconnaissable et le non reconnaissable, la répétition et le bruit.

The industrial revolution was the moment of an unprecedented increase in the extraction and transformation of materials, transformation named objects. This acceleration constituted a libidinal transformation of importance insofar as desire was linked to the rhythm of acquisition of these objects to the point of being constitutive of the very feeling of existence.

The consequence of this process of material and libidinal transformation was the feeling of a permanent déjà vu. When we consumed a cultural object, we had most often the feeling to have already seen it hundreds of times before. This impression of closure of the cultural space was called post-modernism: we could only quote.

A whole generation felt the need to get out of this impasse, for example by appealing to other cultures or by seeking to develop speculative utopias. The reality produced by the industrial production being saturated in advance, it was necessary to impose an exteriority to him so that something can open and that the possible can remain possible.

If one can question the effectiveness of such exteriority, one must notice that the feeling of déjà-vu is at the heart of the latent space of the artificial imagination, because this one, as it is the setting in statistics of millions of documents, is constitutive of a common culture or rather of a common calculability. An image produced by a neural network has never existed, but has always been seen (making the vision of the image independent from an anthropological point of view and not only as a machine of vision), because it is based on the statistics of millions of documents and it is an average of them which is no longer only conceptual but which for the first time makes image. So that the impasse in which the feeling of cultural déjà-vu put us becomes, so to speak, a medium. It is not only a question, as with the pop art, to extract from the media flow some icons or as in the 90s and 2000s, with the postproduction of the cultural objects, to take back the figure of the DJ able to remix something already existing to give a new version and a new perception. It is a question of being based from part to part on what already existed there and one introduces noise to incorporate a light difference there, that it would be necessary rather to name vibration, which allows to create a metastable set between the recognizable repetitive and the strangeness of a possible novelty.

The paradox is that the latent space of the artificial imagination is able to produce the greatest repetition of the déjà-vu as well as the strangest of the differences of the resemblance. With it one can repeat identically certain visual commonplaces of our time or the way our time imagines past times, or one can bend and metamorphose some of these spaces to create monsters which if they are well founded on what already existed, puts in presence unexpected forms. The difference between these two types of déjà-vu is made possible by another cultural latent space which is carried by the person who uses and handles the artificial imagination and who knows or does not know how to articulate the interiority of his cultural and historical latent space to the statistical latent space of the recursive neuron network.

By the same token we leave the epoch of the post-modernism, supposing that we can consider this one in the seriality of an epoch, to enter in another moment that we could name the disrealism and that consists in navigating and getting lost in a latent space so big that it is impossible to have a complete representation of it and that it is only possible to move in it and to find some sub-spaces that have some interests and that know how to maintain a balance between the recognizable and the non-recognizable, the repetition and the noise.