De l’intelligence à l’imagination artificielle / From intelligence to artificial imagination

“Pour apprendre une chose, tu dois commencer par la faire.”

Tim Ingold

Si depuis l’été 2015, et l’apparition des images d’hallucinations psychédéliques de Deep Dream, développées par un ingénieur de Google, les implications culturelles de l’IA sont débattues, c’est bien par la lettre de ChatGPT que le débat s’est enflammé, entrant dans les foyers, les médias sociaux et de masse. Chacun semblant avoir dorénavant un avis sur le sujet et devenant spécialiste des réseaux de neurones artificiels, prédisant un simulacre de facultés humaines, s’étendant de la raison jusqu’à l’imagination, envahissant de façon idiote, morne et statistique jusqu’à ce qui semblait le propre de l’être humain : la peinture, la littérature, l’art. S’ensuivent de mélancoliques discours d’une culture à son crépuscule, dont la modernité nous a abreuvées, défendant le droit aristocratique à l’inutile divagation dans un monde de plus en plus instrumental et dont l’habitabilité se réduit inexorablement.

Or ces critiques participent à la mise en place de cette automatisation et extériorisation des facultés anciennement humaines. Elles mettent en scène l’IA, sa puissance, ses promesses et ses dangers, en s’inspirant de certaines idées préconçues que la SF et le cinéma ont infusées depuis les années 50 dans la culture populaire. Ce qu’on bien compris les GAFAM qui tout en investissant massivement dans des unités de calcul pour IA, fruit de l’extraction minière et de l’exploitation de travailleurs du clic, participent à la mise en place de comités d’éthique et promettent une IA sachant limiter ses biais et son inhumanité, transformant celle-ci en débat de société, pour le pire, mais finalement pour le meilleur.

Ce qui manque à ces dénonciations c’est de s’interroger sur leurs présupposés. On se limite le plus souvent à manipuler ChatGPT, dans un test qui n’est pas au niveau de celui d’Alan Turing, dont l’objectif fixé d’avance est de démontrer la stupidité de la machine. On lui tend des pièges, elle se trompe, réponds à côté. Elle est donc idiote. Par là on suppose que ces logiciels ont comme finalité de nous remplacer et que nous avons autorité à dire sur Terre ce qui est intelligent et ce qui ne l’est pas. D’ailleurs, ce n’est pas le fait du hasard si c’est la possibilité offerte aux étudiants d’automatiser l’écriture de leurs devoirs, faisant perdre aux professeurs leur autorité à évaluer la conformité de l’intelligence, qui a intensifié le débat. Vieille opération consistant à s’attribuer une faculté pour en exclure d’autres non humains : animaux, plantes, minéraux, et finalement peuples exploités et colonisés. Car par une telle répartition des rôles, il s’agit bien de se donner à soi-même une place centrale autour duquel s’organise un environnement de ressources utilisables à son profit. La première cybernétique avait anticipé ce tour de passe-passe : Turing estimait que la pensée n’est rien d’autre qu’un bourdonnement dans la tête et dans la seconde version de son célèbre test, il demandait à un homme et à une machine de mimer une femme dans une tentative désespérée de les mettre à égalité afin que l’humaniste de s’autoattribue pas trop de capacités.

La prophétie du remplacement de l’être humain par la machine développe une précarité dangereuse parce qu’elle remplace l’expérimentation par des idées préconçues. Il n’est pas sûr que l’objectif de l’IA soit de mimer à l’identique nos facultés, comme il est incertain que ces facultés nous soient transparentes et existent sous la forme que nous croyons. Il est tout aussi incertain que l’art ne soit que le produit de la créativité humaine, d’une intériorité soumettant un matériau à sa subjectivité expressive. L’imagination, la faculté de produire des images, n’est-elle pas aujourd’hui comme hier dépendante de supports d’inscription matériels qui sont autant de techniques ? L’artiste, à la manière de Rodin, ne s’adapte-t-il pas tout autant aux aléas du marbre qu’il tente de lui donner forme dans un aller-retour qui est moins un acte de domination qu’un dialogue incessant où chacun se perd dans l’autre ?

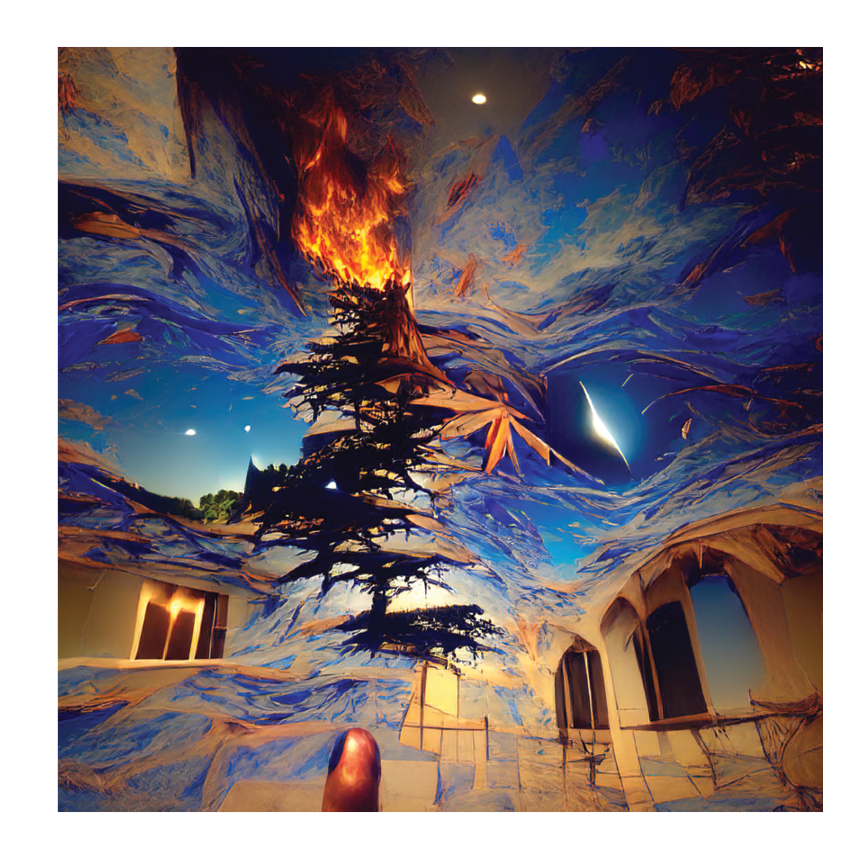

Si l’art peut nous apprendre quelque chose de l’IA, ce n’est pas dans le discours nostalgique et suranné de sa perte, mais dans ce mouvement paradoxal entre l’humain et le non-humain car, comme l’écrivait Apollinaire en 1913, « Avant tout, les artistes sont des hommmes qui veulent devenir inhumains. » Des artistes comme Pierre Huyghe, Trevor Paglen, Hito Steyerl, Fabien Giraud et Raphael Siboni se sont emparés depuis plus d’une décennie de ces imaginations artificielles moins pour les critiquer que pour explorer le monde étrange de l’espace latent qui est fait de ces millions de données accumulées par les êtres humains sur le Web traduit en probabilités, permettant non de citer à l’identique ces documents, mais d’en synthétiser d’autres, ressemblants comme la version alternative du monde connu.

Il est alors peut être temps de remplacer les discours emphatiques, qu’ils soient enthousiastes ou conjuratoires, solutionnistes ou mélancoliques, tissés d’idées préconçues, par l’expérimentation de ces réseaux de neurones que nous influençons et qui transforment notre manière de penser, de percevoir, d’imaginer et de produire des œuvres. Ils métabolisent ce que les êtres humains ont accumulés au fil de leur histoire, traces de leurs fragiles existences, pour nous permettre d’imaginer une nouvelle finitude tissée d’un sentiment d’infinitude : ce monde et tant d’autres, ces réssurections du passé qui sont encore à venirs, à la limite de notre disparition. Peut-être pourrons-nous moins dominer ou être dominés par l’IA que dialoguer avec elle, comme si nous dialoguions avec nous-mêmes, comme avec un autre.

–

If since the summer of 2015, and the appearance of the images of psychedelic hallucinations of Deep Dream, developed by a Google engineer, the cultural implications of AI have been debated, it is indeed by the letter of ChatGPT that the debate has been ignited, entering the homes, social and mass media. Everyone seems to have an opinion on the subject from now on and becomes a specialist in artificial neural networks, predicting a simulacrum of human faculties, extending from reason to imagination, invading in a silly, dull and statistical way even what seemed to be the proper of the human being: painting, literature, art. There follow melancholic speeches of a culture in its twilight, of which modernity abounded us, defending the aristocratic right to the useless rambling in a world more and more instrumental and whose habitability is inexorably reduced.

But these criticisms participate in the implementation of this automation and exteriorization of the formerly human faculties. They stage AI, its power, its promises and its dangers, drawing on certain preconceived ideas that SF and the cinema have infused into popular culture since the 1950s. GAFAM have understood this well, and while investing massively in computing units for AI, fruit of mining and exploitation of click workers, they participate in the setting up of ethics committees and promise an AI that knows how to limit its biases and inhumanity, transforming this one into a social debate, for the worst, but finally for the best.

What is missing in these denunciations is to question their presuppositions. Most of the time, we limit ourselves to manipulating ChatGPT, in a test that is not at the level of Alan Turing’s, whose objective is to demonstrate the stupidity of the machine. We set traps for it, it makes mistakes, answers wrong. It is therefore stupid. By this we suppose that these softwares have the aim to replace us and that we have the authority to say on Earth what is intelligent and what is not. Moreover, it is not by chance that it is the possibility offered to students to automate the writing of their assignments, making teachers lose their authority to evaluate the conformity of intelligence, that has intensified the debate. The old operation of attributing a faculty to oneself in order to exclude other non-human faculties: animals, plants, minerals, and finally exploited and colonized peoples. For by such a distribution of roles, it is indeed a question of giving oneself a central place around which an environment of resources usable for one’s benefit is organized. The first cybernetics had anticipated this trick: Turing considered that thought is nothing but a buzzing in the head and in the second version of his famous test, he asked a man and a machine to mimic a woman in a desperate attempt to put them on an equal footing so that the humanist would not attribute too many capacities to himself.

The prophecy of the replacement of the human being by the machine develops a dangerous precariousness because it replaces experimentation by preconceived ideas. It is not certain that the objective of AI is to mimic our faculties identically, just as it is uncertain that these faculties are transparent to us and exist in the form we believe. It is also uncertain that art is only the product of human creativity, of an interiority subjecting a material to its expressive subjectivity. The imagination, the faculty to produce images, is it not today as yesterday dependent on material supports of inscription which are so many techniques? The artist, in the manner of Rodin, does he not adapt as much to the hazards of the marble that he tries to give him form in a back and forth which is less an act of domination than an unceasing dialogue where each one loses himself in the other?

If art can teach us anything about AI, it is not in the nostalgic and outdated discourse of its loss, but in this paradoxical movement between the human and the non-human because, as Apollinaire wrote in 1913, “Above all, artists are men who want to become inhuman.” Artists like Pierre Huyghe, Trevor Paglen, Hito Steyerl, Fabien Giraud and Raphael Siboni have been seizing for more than a decade these artificial imaginations less to criticize them than to explore the strange world of latent space that is made of these millions of data accumulated by human beings on the Web translated into probabilities, allowing not to quote identically these documents, but to synthesize others, resembling them as the alternative version of the known world.

It may be time to replace emphatic speeches, whether enthusiastic or conjuring, solutionist or melancholic, woven with preconceived ideas, by the experimentation of these neural networks that we influence and that transform our way of thinking, perceiving, imagining and producing works. They metabolize what human beings have accumulated throughout their history, traces of their fragile existences, to allow us to imagine a new finitude woven with a feeling of infinity: this world and so many others, these resurrections of the past that are still to come, at the limit of our disappearance. Perhaps we will be able to dominate or be dominated less by AI than to dialogue with it, as if we were dialoguing with ourselves, as with another.