Disruption as denial of extinction

In all technology conferences, the word “disruption” has come up again and again in recent years. It is like a watchword that everyone repeats, passing from one mouth to the other. It designates an innovation that would radically change the order we know. To illustrate it, we often talk about Steve Jobs comparing him to a real artist or Elon Musk, genius of our time. Between the intensity with which this word is charged and the emptiness of the examples given, there is the difference of an expectation.

There is such a difference between the word and the phenomena (Adidas’ latest campaign has the most beautiful comic effect) that it can only mean a will that something will happen and finally change, a break. Even if this is not said, the feeling that is going through the disruption is that the world is going badly and that we can no longer continue like this. It is also about a “revolutionary” desire that refuses the status quo. Speakers felt that companies (and sometimes states) are not doing enough and that we would have the opportunity to change everything when we are only incrementally innovating. We only invent gadgets when we could reconfigure the world. A little will that hell! But crying out in this way, they do not know what the content of the disruption would be. The feeling of standing still is endless: rupture as a reaction.

What is most astonishing is the simultaneity of the emptiness of the word and its emotional power. His point is the singularism of Ray Kurzweil, affectivity without phenomenological content, whose only attraction is to fanstamer the victory against the indeconstructible.

There is humour in giving responsibility for such a grandiose change to individuals, entrepreneurs, whose conservatism is often equalled only by the will to accumulate, and who are responsible for much of the situation in which we find ourselves. They are the poison and the remedy according to the ambivalent logic of the pharmakon (φαρμακός). There is something comical in reading the writings of these individuals who scroll through common theological places and advertising phraseology. There is the immense burst of laughter in front of the enthusiasm triggered by Elon Musk, his dreams à la Jules Vernes and his poorly articulated reflection (you have to hear one of his interventions to believe it!). The most absurd solutionism reigns: for example, we explain that AI is energy-intensive, that it must therefore be made greener and that by this very fact we can solve the ecological transition and all the ecological problems we face. I summarize: 1) X poses a problem 2) We solve the problem posed by X 3) The whole problem, which goes beyond the order of magnitude of X, is thereby solved.

This age of mediocrity signals a desire to believe, a will going as far as the absurd to find a great narrative, myths, an imaginary, a will that is parallel to a return of religion that also promises the organization of a world order and an end point that is also a point of origin. Between the two is probably the idea of the “last god”. That one can be enthusiastic for such empty speeches, for such non-existent and unreflexive concepts is the symptom of a desire that finds no better way to incarnate.

Disruption is empty of phenomenon, but full of meaning, it expresses a deep tension: something must happen and everything must change. This change in the course of things is theological and reproduces the great religious narratives of the apocalypse and the resurrection. One can delegate, no longer to the divine, but to the private economy and to technologies (these are two figures of completed metaphysics) this immense task, in either case it conceals its object. We promise to fix everything, we dream of THE solution, but we have no idea what it should be. Then maybe someone, anyone, will find the trick. Do we ever know?

The discourse of disruption metabolizes revolutionary desire in another organism: the liberal economy. It makes it possible to conceal the present reality whose urgency does not consist in finding THE solution, but in settling precise sufferings. Faced with the multiplication of the latter, there is no doubt that the forced march demanded by the disruption is similar to a headlong rush: especially not to turn around and change anything. For example, rethinking the relationship between state, company and common, tracing lines of division and responsibilities, this is what the disruption does not want.

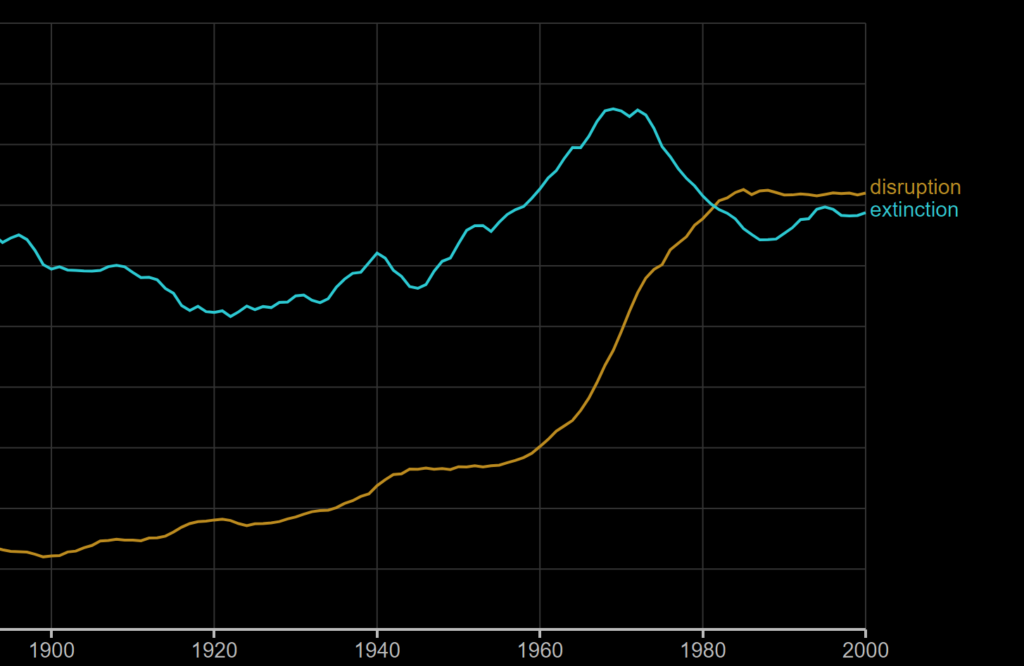

But, by going further, we can also think that this discourse of disruption dreams of a radical event that would break with everything and that would be the fruit of the human will of a disruptor (inventor, entrepreneur, startuper, etc.) Now, it is about a reappropriation and an occultation of an event much less distant and much less human, extinction. For how can we not laugh at the gap between the pathos of the disruptors-entrepreneurs promising us mount and marvel without advancing anything except consumer objects further aggravating spiritual and material situations, and the silent pathos of such species, such people, such landscape, such resources, down to the last human being. This extinction is not theological, at least not only if it is not apocalyptic, because contradictory scientific data and studies are available. We are promised an immense change through technological disruption, but why this immobility in the face of extinction? The judgment seems to have no rationality.

Behind the disruption as well as behind the denial of extinction lies the same demiurgical desire to end finitude. To end finally with death, and with the living, with the body, and with the living, with the contingency, and with the living, with all that we are. Singularity, as the finished form of disruption since it disrupts the disruptor itself, is similar to an extinction of the species and is not the result of chance. We hide the death of the sun (If we can think without bodies where Lyotard criticises the Singularity theory in advance) by a death voluntarily organised by human beings, a death that would also be the promise of eternal survival. Behind the great discourses of disruption which drap themselves in good feelings and which even want to take charge of the commons (!) hides the arrogance of individuals who want to regulate the lives of others, immaturity which refuses mortality, and also finally a flight forward which is an immobilism and which puts at stake the conditions of survival of the human species.