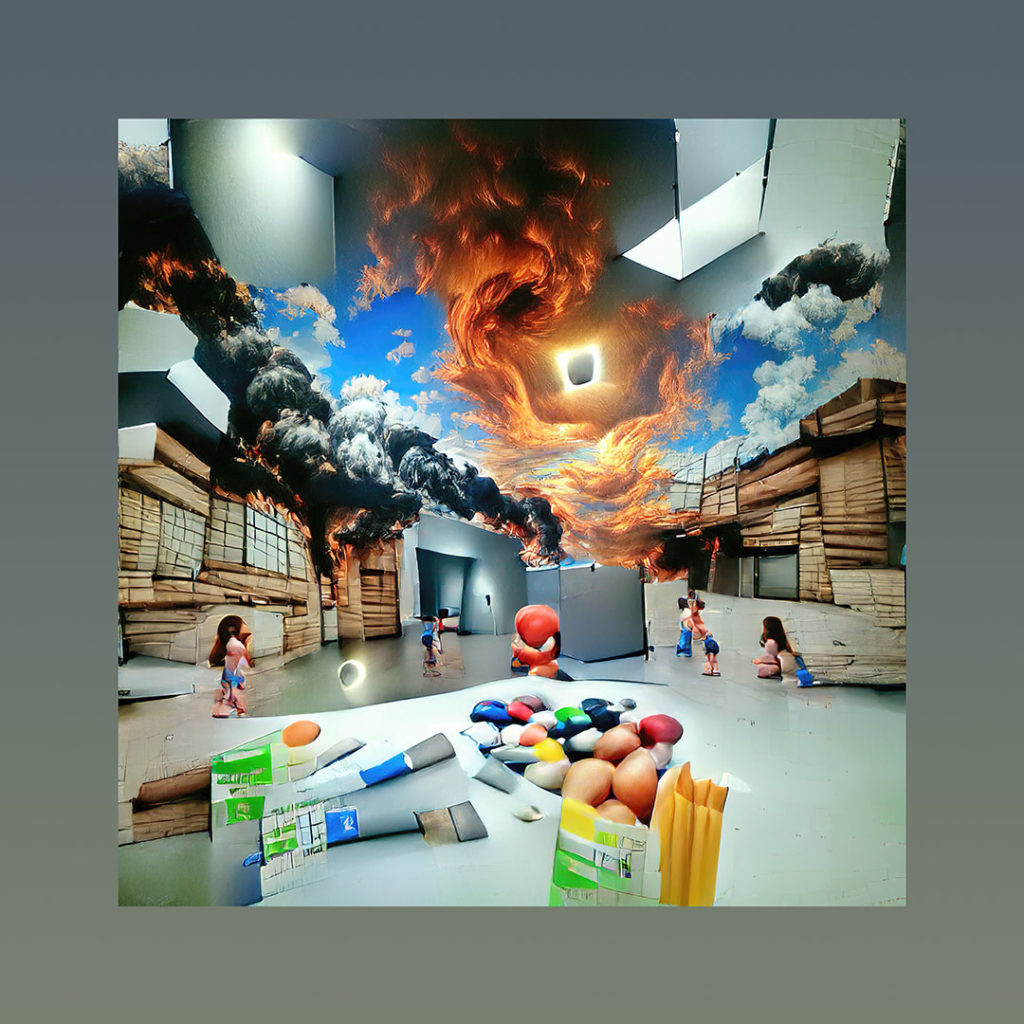

Terre des spectres / Earth of Specters

Il y a quelque chose de saisissant en ce que le pétrole et le charbon sont le résultat de la décomposition d’une matière animale et d’une matière végétale. La consumation des fossiles énergétiques, qui mettent en jeu les conditions d’habitation terrestre pour les vivants, sont précisément des fossiles du vivant. Nous les brulons et cette chaleur se répand sur l’atmosphère.

Il y a là un échange trouble entre tous les vivants passés et les vivants futurs, comme si cette résurrection (bruler le passé) était une insurrection (bruler le futur).

Dans un récent article de la revue Nature (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03821-8), des chercheurs estiment qu’il faudrait laisser entre 60 et 80 % du pétrole et du charbon sous terre pour maintenir un cap de réchauffement raisonnable. Cette part inextractible m’évoque l’image de quelque chose qu’on ne devrait pas déterrer pour ne pas être enterré, comme la hantise inextricable de tout ce qui nous a précédés et que nous cherchons, depuis la révolution industrielle, à consumer.

Nous brulons les animaux et les végétaux qui nous précédent. Cette consumation nous consume. Il y a là sans doute une autre conception de l’histoire, de la relation entre le passé et le futur. Ce n’est pas que ce dernier fait table rase du premier, mais qu’il le brule, il n’est que sa brulure.

Je ne peux m’empêcher d’y associer une autre structure temporelle. Celle ouverte par l’induction statistique des réseaux de neurones qui, précisément, produisent du « nouveau » en traitant des stocks d’informations passées. Le possible, en tant qu’à venir, n’est rendu possible que par cette métabolisation qui se dévore. Ce corps étrange ne se nourrit que pour résister à sa propre dévoration : un corps qui ne mange pas d’autres organismes se mange lui-même.

There is something striking in the fact that oil and coal are the result of the decomposition of animal and vegetable matter. The burning of energetic fossils, which bring into play the conditions of terrestrial habitation for the living, are precisely fossils of the living. We burn them and this heat spreads on the atmosphere.

There is a turbulent exchange between all past living and future living, as if this resurrection (burning the past) were an insurrection (burning the future).

In a recent article in the journal Nature (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03821-8), researchers estimate that we would have to leave between 60 and 80% of oil and coal underground to maintain a reasonable warming course. This inextractable portion evokes for me the image of something that should not be dug up to avoid being buried, like the inextricable haunting of everything that came before us and that we have sought, since the industrial revolution, to consume.

We burn the animals and the plants that precede us. This consumption consumes us. There is undoubtedly another conception of history, of the relation between the past and the future. It is not that the latter makes a clean sweep of the former, but that it burns it, it is only its burning.

I cannot help but associate another temporal structure with it. The one opened by the statistical induction of neural networks which, precisely, produce the “new” by processing stocks of past information. The possible, as being to come, is only made possible by this metabolization that devours itself. This strange body feeds itself only to resist its own devouring: a body that does not eat other organisms eats itself.