Nostparôn

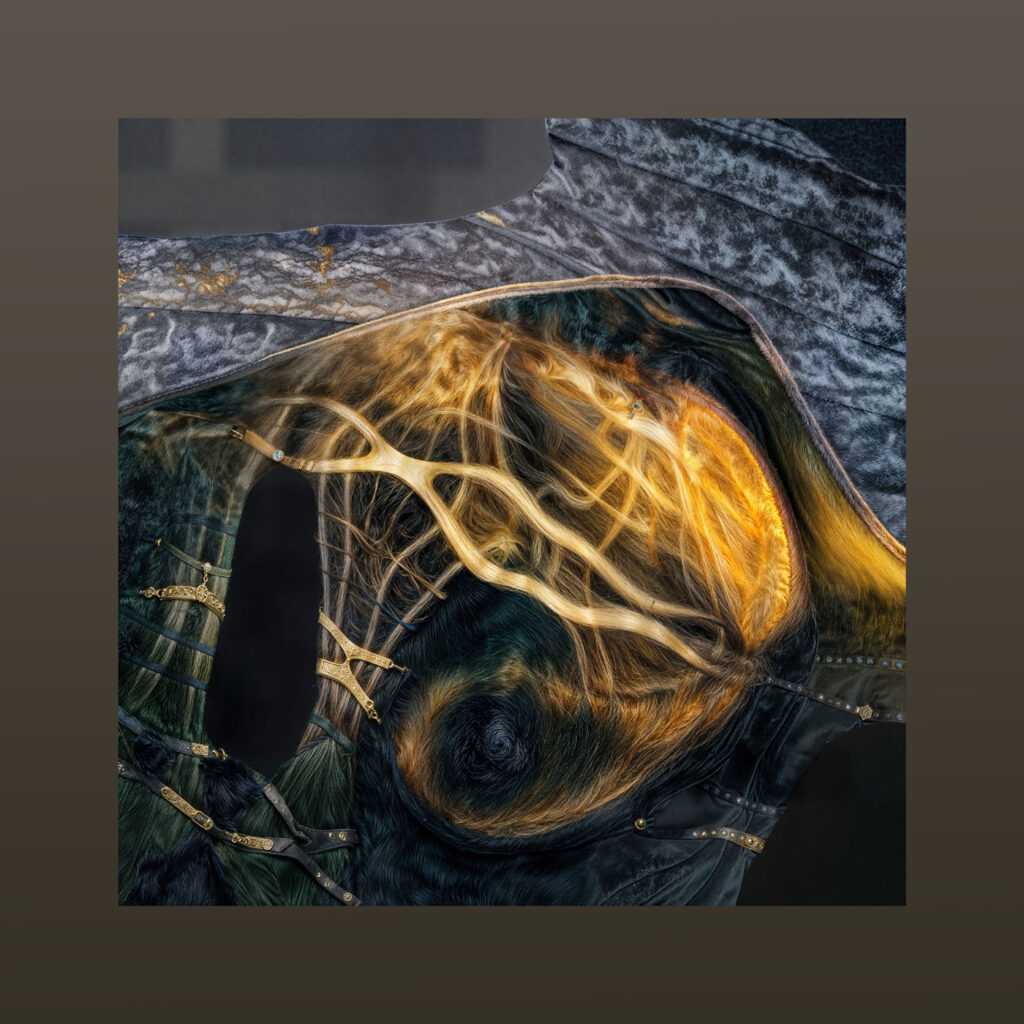

De nombreux artistes et créatifs manifestent une nostalgie surprenante envers des technologies génératives extrêmement récentes. Ce phénomène se cristallise particulièrement autour de l’esthétique des GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks), caractérisée par ses qualités fluxionnelles et métamorphiques, ainsi que ses imperfections pixellisées. Cette nostalgie paradoxale révèle un schéma récurrent : chaque avancée technologique est perçue simultanément comme un progrès technique et comme une perte esthétique. Les défauts techniques, initialement considérés comme des limitations, sont rétrospectivement valorisés pour leur richesse plastique. L’amélioration des modèles apparaît alors comme un processus de standardisation qui, en éliminant ces “imperfections créatives”, conduit à une normalisation croissante des productions artistiques.

La temporalité des technologies d’IA génératives présente une particularité notable : bien que leur démocratisation soit très récente (2015 pour la génération d’images, 2019 pour les textes), leur intégration dans nos pratiques numériques a été si rapide et profonde qu’elle a créé une rupture dans notre relation à l’informatique. Cette rupture se manifeste par une double difficulté : nous peinons à nous remémorer précisément nos pratiques numériques antérieures, tout en étant incapables d’imaginer un retour à un fonctionnement sans ces outils. Cette amnésie sélective du “monde d’avant” témoigne de la puissance transformative de ces technologies sur nos habitudes cognitives et créatives. Tout se passe comme si les IA génératives avaient toujours été là parce qu’elles sont le résultat de ce qui précède.

Le concept de nostparôn, néologisme construit à partir du grec ancien νόστος (nóstos, “retour”) et παρών (parôn, “présent”), propose un cadre théorique pour appréhender cette tension temporelle inédite. Cette construction étymologique permet de conceptualiser un nouveau type de nostalgie qui se distingue des formes traditionnelles par son rapport au temps.

Le nostparôn se différencie fondamentalement de la nostalgie en ce qu’il opère principalement dans la dimension temporelle plutôt que spatiale. Sa spécificité réside dans son attention au “tout juste passé” (plutôt que le présent comme dans le cas de la solastalgie), créant un paradoxe temporel où l’obsolescence technique immédiate transforme le passé proche en objet de désir. Ce phénomène s’explique par deux dynamiques convergentes : d’une part, le rythme d’évolution technologique dépasse notre capacité d’adaptation et d’appropriation cognitive ; d’autre part, la mémoire émotionnelle associée aux découvertes récentes entre en conflit avec l’injonction permanente au renouvellement technologique.

La vitesse d’innovation crée ainsi une dissonance entre le rythme technologique et nos temporalités anthropologiques (gestes, habitudes, attention). Cette tension empêche l’établissement d’une véritable époché phénoménologique, donnant naissance à cet affect particulier qu’est le nostparôn.

Ce nouveau rapport au temps ne peut être réduit à une simple nostalgie du pays natal ou d’un passé idéalisé. Il constitue plutôt une modalité inédite du rapport au passé récent, qui refuse de “passer” au sens traditionnel. Cette perturbation temporelle affecte profondément notre constitution historique : le passé persiste anormalement, le futur semble inaccessible, et le présent devient insaisissable. Ces formulations négatives ne sont pas une simple limitation linguistique mais reflètent la nécessité de développer un nouveau cadre conceptuel pour appréhender cette temporalité émergente et l’historicité qu’elle engendre.

Cette reconfiguration de notre expérience temporelle appelle à une réflexion approfondie sur les implications anthropologiques, esthétiques et philosophiques de notre relation aux technologies génératives et, plus largement, à l’accélération technologique contemporaine.

Many artists and designers are showing a surprising nostalgia for extremely recent generative technologies. This phenomenon crystallizes particularly around the aesthetics of GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks), characterized by their fluxional and metamorphic qualities, as well as their pixelated imperfections. This paradoxical nostalgia reveals a recurring pattern: every technological advance is perceived simultaneously as technical progress and aesthetic loss. Technical flaws, initially seen as limitations, are retrospectively valued for their plastic richness. Model improvement then appears as a standardization process which, by eliminating these “creative imperfections”, leads to an increasing standardization of artistic productions.

The temporality of generative AI technologies presents a notable peculiarity: although their democratization is very recent (2015 for image generation, 2019 for text), their integration into our digital practices has been so rapid and profound that it has created a rupture in our relationship to computing. This rupture manifests itself in a double difficulty: we find it hard to recall precisely our previous digital practices, while at the same time being unable to imagine a return to functioning without these tools. This selective amnesia of the “world before” testifies to the transformative power of these technologies on our cognitive and creative habits. It’s as if generative AIs have always been there, because they are the result of what came before.

The concept of nostparôn, a neologism constructed from the ancient Greek νόστος (nóstos, “return”) and παρών (parôn, “present”), offers a theoretical framework for apprehending this novel temporal tension. This etymological construction allows us to conceptualize a new type of nostalgia that differs from traditional forms in its relationship to time.

Nostparôn differs fundamentally from nostalgia in that it operates primarily in the temporal rather than the spatial dimension. Its specificity lies in its focus on the “just past” (rather than the present as in the case of solastalgia), creating a temporal paradox where immediate technical obsolescence transforms the near past into an object of desire. This phenomenon can be explained by two converging dynamics: on the one hand, the pace of technological evolution outstrips our capacity for adaptation and cognitive appropriation; on the other, the emotional memory associated with recent discoveries comes into conflict with the permanent injunction to technological renewal.

The speed of innovation thus creates a dissonance between the technological rhythm and our anthropological temporalities (gestures, habits, attention). This tension prevents the establishment of a genuine phenomenological epoch, giving rise to that particular affect known as nostparôn.

This new relationship with time cannot be reduced to a simple nostalgia for the homeland or an idealized past. Rather, it is a new way of relating to the recent past, which refuses to “pass” in the traditional sense. This temporal disruption profoundly affects our historical constitution: the past persists unnaturally, the future seems inaccessible, and the present becomes elusive. These negative formulations are not simply a linguistic limitation, but reflect the need to develop a new conceptual framework to apprehend this emerging temporality and the historicity it engenders.

This reconfiguration of our temporal experience calls for in-depth reflection on the anthropological, aesthetic and philosophical implications of our relationship to generative technologies and, more broadly, to contemporary technological acceleration.