Mémoire seconde / Memory second – Julien des Monstiers

Texte écrit à l’occasion de l’exposition de Julien de Monstiers à la galerie Christophe Gaillard.

https://galeriegaillard.com/en//artists/8522-julien-des-monstiers/works/

Je suivais depuis des années son travail, admiratif de sa maitrise d’une banalité picturale parvenant à lui donner une seconde vie, une seconde peau. J’ignorais qu’il me suivait également à la trace, comme dans une histoire où deux détectives auraient été payés par un même commanditaire pour s’observer en ignorant la parité de leur mission. Nous connaissions nos travaux sans nous connaître. Sans doute nous partagions un rapport aux images, influence sourde et constante, comme la noise d’un reflux, sur nos existences. Je n’avais ni l’autorité ni le prestige d’un critique d’art ou d’un philosophe pour écrire un texte. J’étais comme lui, je faisais des images.

J’avais admiré la reprise de motifs classiques qui avaient eu leur heure de gloire et qui semblaient à présent un peu kitsch et néo parce que délaissé. Il aimait les remettre en selle comme si cela avait été la première fois. Il y avait ces scènes champêtres et de chasse qu’on imagine délavées sur le papier peint de maisons humides.Comment ramener à la vie ce qui a été délaissé ? Comment rendre justice à un monde en train de disparaître ? Comment ouvrir des maisons depuis longtemps abandonnées ?

La stratégie picturale est la même et elle est paradoxale en faisant de l’image quelque chose de bifide. Il y a bien sûr cette picturalité réaliste et précise, appliquée même, qui semble appartenir à un régime classique et puis comme superposé, on ne sait si c’est devant ou en fond, sans doute est-ce les deux à la fois, il y a des motifs plus abstraits qui reprennent un vocabulaire quasi moderniste. Cette superposition permet d’articuler deux traditions que le sens commun oppose alors que leur développement historique est commun depuis Fra Angelico, sans doute avant. D’un côté, la représentation asservie au mimétisme, de l’autre l’abstraction autonome se prenant pour sa propre fin. On connaît ce discours jusqu’à la nausée. Ici, tout se passe comme si, sur ces figures trop vues et laissées de côté, on plaçait un motif visuel pour refiltrer l’expérience visuelle. Dans la jointure désaccordée entre les deux se joue non seulement une approche transcendantale du pictural, c’est-à-dire des conditions de possibilités du visible, mais aussi une transformation de l’historicité même des images. On montre que devant et derrière la représentation, il y a du motif autonome et que celui-ci est travaillé par la représentation. La relation entre les deux est inextricablement construite et contingente. Ce sont alors deux époques passées qui se superposent, le classicisme et la modernité, parce que le présent c’est précisément leur dis-jointure anachronique et intempestive. C’est elle qui permet de voir l’image dans son processus perceptif et historique en train de naître et de disparaître, dans un flux et un reflux. L’afflux c’est précisément l’excès de peinture, qui dégouline, qui fait tache. Le présent comme deux passés qui ne se correspondent pas, mais qui coexistent.

Ce filtre pictural n’est pas seulement devant l’image, parce qu’elle est une structure et un geste. Le quadrillage, les aplats c’est ce qui fait advenir très concrètement l’image dans le travail de l’atelier. La genèse de l’image est placée au-devant, de sorte que paradoxalement elle obstrue ce qu’il y a à voir et crée partout des hors champ comme si la vision devenait scintillante. C’est cette cache-picturale qui forme la singularité du tableau, car elle voile et dévoile, elle est la palpitation du temps.

J’aimerais imaginer que le rapport entre ces deux régimes picturaux soit inextricablement une érosion et une germination, deux phénomènes qui travaillent la matière en la détruisant et en la faisant apparaître. L’histoire des êtres humains n’aura été celle que d’habiter l’érosion qui dessine la planète. Les tableaux sont des images érodées par le temps et l’histoire, par le trop vu. Il y a une érosion de la perception qui est ici présentée à elle-même, dans sa duplicité.

Une image érodée, ce pourrait être cette encyclopédie dans laquelle on se plongeait enfant et qui permettait de tenir entre ses petits bras un espace plus grand que soi, un monde qui par définition excède le champ de la perception. Bord du monde et reliure du livre. Tenir ce grand livre c’était une manière de craquer une allumette et de jouir de sa consumation pour rien, pour la joie de la dissipation elle-même, voir la transformation du bois jusqu’à la disparition de sa forme. L’enfant sait bien que ce n’est pas vraiment tout l’univers, mais, comme dans le tableau, se superpose l’univers et les pages qu’on tient en main. Il fallait donc reprendre cet ouvrage, reproduire sa typographie le plus méticuleusement possible en effectuant un retournement surprenant puisque l’image de la représentation (la couverture du livre) passe maintenant au premier plan. Voilà pour l’origine la peinture. S’il y a du texte, il n’est pas langagier, il est encore pictural et le rouge se change en un or comme s’il était consumé du dessous. Pour soutenir cette encyclopédie, il a fallu des générations et des générations, elle était déjà dépassée pendant l’enfance du peintre, on n’en a gardé comme reliques et ossuaires que les dents.

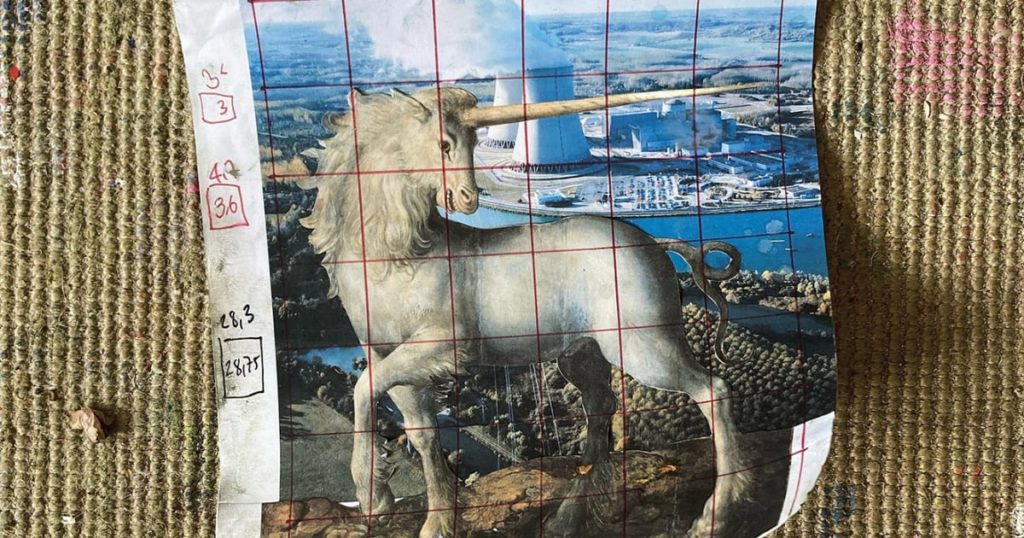

On reprend, en vue de la réinitialiser, une figure qui appartient au classicisme et à l’imagerie contemporaine, la licorne dans le genre chasse. Tout comme cet animal mythique, la centrale nucléaire est éternelle parce que la toxicité des déchets durera plus longtemps que l’existence même de l’espèce humaine. Là encore le temps. On donne à ce mème une nouvelle vie, une nouvelle chance, une nouvelle scène, celle des temps profonds de la Terre qui sont simplement effleurés par quelques lignes : des ridules, des érosions, des craquelures venant défaire l’image pour la faire enfin advenir.

Il y a ce village en vue cavalière où c’est le ciel qui descend sur Terre comme si le bleu atterrissait au sol. Ce n’est pas l’atterrissage de Bruno Latour, ces nouveaux enracinement et attachement, mais l’élévation du ciel sur la terre, car s’il y a un autre monde, il est dans celui-ci. Le ciel aussi est une source d’érosion. Les éléments ne sont pas séparés, ils circulent des nuages, à l’eau, au minéral et végétal, jusqu’à nous, jusqu’à ce monde-ci dans lequel nous habitons. La vision est scintillante et le crâne vacille devant l’étendue mélangée.

Loin des cabanes imaginées par ceux qui rêvent de fuir les villes, les abris sont ici de fortune, ce sont ceux des habitants d’un village. Ils sont précaires, car habiter ce n’est pas s’enraciner, c’est faire le deuil de toute territorialité et les planches sont disjointes, comme la peinture, on voit à travers, comme si les motifs picturaux au-dessus étaient eux-mêmes des planches disjointes, d’un autre abri, peut être l’atelier de l’artiste, brouillant un peu plus ce qui est dedans et dehors. Là encore, il s’agit de donner une seconde vie à ces images déjà vues. La mémoire vive n’est pas une mémoire vivante, ce vitalisme aujourd’hui omniprésent, c’est une mémoire ressuscitée, car la vie n’est pas quelque chose de naturel, c’est une seconde fois qui rend justice à ce que nous avons abandonné. Précisément, ces abris sont sans doute laissés à eux-mêmes et inhabités. On retrouve donc les traces d’érosion devenues telluriques, bouchant l’espace, l’occultant comme si on était soi-même protégé dans une cabane abandonnée. L’image brûle, elle s’abîme, mais son défaut est originaire, car c’est sa structure, c’est ce qui la rend possible. L’altération ne vient pas dans un second temps, elle est originaire, une souffrance qui est antérieure à toute expérience.

Ces 30 dernières années ont été marquées par une accumulation sans borne de mémoire, de sorte que plus qu’aucune autre époque historique nous vivons au milieu des archives que nous n’arrivons plus même à consulter. Notre mémoire humaine n’est plus humainement accessible. L’hypermnésie du réseau a envahi nos existences jusqu’à ce que toute image soit déjà trop vue. La peinture a peut-être ce privilège par l’inscription de son temps au travail, de donner à voir une mémoire vive, c’est-à-dire une résurrection qui serait aussi une première fois. Il ne s’agit donc pas de kitsch ou de reprise, de postmodernisme, que sais-je encore, mais par la superposition de la représentation et du motif de faire en sorte que l’image naisse, dans sa naissance même se corrompe et que la corruption soit la condition de sa naissance.

Il n’y a dans cette autre mémoire aucun naturalisme, car les abris, la licorne ou le village vu du ciel ne sont pas des appels à un passé bucolique glorieux. Il s’agit en fait de répéter, c’est-à-dire de revenir encore et encore sur le motif, comme on tourne les pages d’une encyclopédie trop lourde, pour préserver ce qui est en train de disparaître et qui est devenu obsolète. Dans certains dialogues platoniciens, le prologue est étrange : quelqu’un rencontre une connaissance dans les rues d’Athènes et lui raconte qu’il vient de croiser un autre de ses amis qui lui a raconté un repas qui a eu lieu la veille, repas dont il va narrer les échanges animés et contradictoires. Pourquoi Platon introduit-il son récit par une telle chaîne de transmission, alors qu’il aurait été plus simple de faire un récit au premier degré ? C’est que le texte qu’il est en train d’écrire sur un support matériel va être corrompu par le passage du temps alors même qu’il souhaite communiquer des formes idéales et incorruptibles. Comment préserver ces images de pensée de la corruption de la matière ? Platon corrompt son idée dès l’origine, elle est un récit rapporté au deuxième ou au troisième degré de sorte qu’on ne peut être sûr de sa véracité. Comme l’idée est toujours déjà corrompue, plus aucune corruption ultérieure ne pourra venir en modifier la nature. L’image dégradée et érodée permet de rendre justice à aux images oubliées, de les faire revenir à notre mémoire dans leur effacement même comme un adieu à un monde dont l’ombre portée durera plus longtemps que la vie même.

–

I had been following his work for years, admiring his mastery of a pictorial banality that managed to give him a second life, a second skin. I was unaware that he was also following me, as in a story where two detectives would have been paid by the same sponsor to observe each other while ignoring the parity of their mission. We knew our work without knowing each other. Without a doubt we shared a relationship with images, a dull and constant influence, like the noise of an ebb, on our existences. I had neither the authority nor the prestige of an art critic or a philosopher to write a text. I was like him, I made images.

I had admired the revival of classic motifs that had had their day and now seemed a bit kitschy and neo because they had been abandoned. He liked to put them back in the saddle as if it had been the first time. There were these country and hunting scenes that one imagines faded on the wallpaper of damp houses. How to bring back to life what has been neglected? How do you bring back to life what has been abandoned? How do you do justice to a world that is disappearing? How to open houses long abandoned?

The pictorial strategy is the same and it is paradoxical by making the image something bifid. There is of course this realistic and precise pictoriality, even applied, which seems to belong to a classical regime and then as if superimposed, we do not know if it is in front or in the background, probably it is both at the same time, there are more abstract motifs which take up a quasi modernist vocabulary. This superimposition makes it possible to articulate two traditions that common sense opposes whereas their historical development is common since Fra Angelico, probably before. On the one hand, the representation enslaved to mimicry, on the other hand the autonomous abstraction taking itself for its own end. We know this discourse to the point of nausea. Here, everything happens as if, on these figures too seen and left aside, one placed a visual motive to refilter the visual experience. In the detuned joint between the two, not only is a transcendental approach to the pictorial played out, that is to say, to the conditions of possibility of the visible, but also a transformation of the very historicity of images. It is shown that in front of and behind the representation, there is an autonomous motif and that this one is worked by the representation. The relation between the two is inextricably constructed and contingent. It is then two past times which are superimposed, the classicism and the modernity, because the present it is precisely their anachronistic and inopportune dis-junction. It is the present that allows us to see the image in its perceptive and historical process in the process of being born and disappearing, in an ebb and flow. The influx is precisely the excess of painting, which drips, which stains. The present as two pasts that do not correspond, but which coexist.

This pictorial filter is not only in front of the image, because it is a structure and a gesture. The grid, the flat tints, is what makes the image happen very concretely in the work of the studio. The genesis of the image is placed in front, so that paradoxically it obstructs what there is to see and creates off-screen areas everywhere, as if vision were becoming scintillating. It is this pictorial concealment that forms the singularity of the painting, because it veils and reveals, it is the palpitation of time.

I would like to imagine that the relationship between these two pictorial regimes is inextricably an erosion and a germination, two phenomena that work the matter by destroying it and making it appear. The history of human beings will have been that of inhabiting the erosion that draws the planet. The paintings are images eroded by time and history, by the too much seen. There is an erosion of the perception which is presented here to itself, in its duplicity.

An eroded image, it could be this encyclopaedia in which one plunged as a child and which made it possible to hold between its small arms a space larger than oneself, a world which by definition exceeds the field of the perception. Edge of the world and binding of the book. Holding this big book was a way to strike a match and enjoy its burning for nothing, for the joy of the dissipation itself, to see the transformation of the wood until its form disappears. The child knows well that it is not really the whole universe, but, as in the painting, the universe and the pages that one holds in hand are superimposed. It was therefore necessary to take up this work, to reproduce its typography as meticulously as possible by carrying out a surprising reversal since the image of the representation (the cover of the book) now passes to the foreground. So much for the origin of the painting. If there is text, it is not linguistic, it is still pictorial and the red changes into a gold as if it were consumed from below. To support this encyclopedia, it took generations and generations, it was already outdated during the childhood of the painter, one kept of it as relics and ossuaries only the teeth.

In order to reinitialize it, a figure that belongs to classicism and contemporary imagery, the unicorn in the hunting genre, is taken up again. Like this mythical animal, the nuclear power plant is eternal because the toxicity of the waste will last longer than the very existence of the human species. Again, time. We give this meme a new life, a new chance, a new scene, that of the deep times of the Earth which are simply touched by a few lines: wrinkles, erosions, cracks coming to undo the image to make it finally happen.

There is this village in a bird’s eye view where it is the sky that descends to Earth as if the blue were landing on the ground. This is not Bruno Latour’s landing, these new roots and attachments, but the elevation of the sky on the earth, because if there is another world, it is in this one. The sky too is a source of erosion. The elements are not separated, they circulate from the clouds, to the water, to the mineral and vegetable, to us, to this world in which we live. The vision is scintillating and the skull flickers in front of the mixed expanse.

Far from the huts imagined by those who dream of fleeing the cities, the shelters here are makeshift, those of the inhabitants of a village. They are precarious, because to live is not to take root, it is to mourn any territoriality and the boards are disjointed, like the painting, we see through, as if the pictorial motifs above were themselves disjointed boards, of another shelter, perhaps the artist’s studio, blurring a little more what is inside and outside. Here again, it is a matter of giving a second life to these images already seen. The living memory is not a living memory, this vitalism today omnipresent, it is a resurrected memory, because life is not something natural, it is a second time that does justice to what we have abandoned. Precisely, these shelters are probably left to themselves and uninhabited. We find the traces of erosion that have become telluric, blocking the space, obscuring it as if we were ourselves protected in an abandoned hut. The image burns, it is damaged, but its defect is original, because it is its structure, it is what makes it possible. The alteration does not come in a second time, it is original, a suffering which is anterior to any experience.

These last 30 years have been marked by a boundless accumulation of memory, so that more than any other historical period we live in the middle of archives that we can no longer even consult. Our human memory is no longer humanly accessible. The hypermnesia of the network has invaded our existences until any image is already too much seen. Painting has perhaps this privilege by the inscription of its time at work, to give to see a living memory, that is to say a resurrection which would be also a first time. It is thus not a question of kitsch or of resumption, of postmodernism, what do I know, but by the superposition of the representation and the motive to make so that the image is born, in its birth even corrupts itself and that the corruption is the condition of its birth.

There is no naturalism in this other memory, because the shelters, the unicorn or the village seen from the sky are not appeals to a glorious bucolic past. It is in fact a question of repeating, that is to say of returning again and again to the motif, as one turns the pages of an encyclopedia that is too heavy, to preserve what is disappearing and has become obsolete. In some Platonic dialogues, the prologue is strange: someone meets an acquaintance in the streets of Athens and tells him that he has just met another friend of his who told him about a meal that took place the day before, a meal whose animated and contradictory exchanges he is going to narrate. Why does Plato introduce his story with such a chain of transmission, when it would have been simpler to tell it in the first degree ? It is because the text he is writing on a material support will be corrupted by the passage of time, even though he wishes to communicate ideal and incorruptible forms. How to preserve these images of thought from the corruption of matter ? Plato corrupts his idea from the beginning, it is a second or third degree account so that one cannot be sure of its veracity. As the idea is always already corrupted, no further corruption can change its nature. The degraded and eroded image allows us to do justice to forgotten images, to bring them back to our memory in their very erasure, as a farewell to a world whose shadow will last longer than life itself.