Le bruit et le pastiche : le surréalisme et le pop art comme précurseurs du contexte culturel de l’induction statistique / Noise and Pastiche: Surrealism and Pop Art as Precursors of the Cultural Context of Statistical Induction

Le surréalisme constitue une première lignée de la modernité qui a valorisé le pouvoir créateur, l’inconscient, le rêve et les états d’hallucination provoquée, tout en s’intéressant paradoxalement aux machines et en proposant de mettre en rapport l’automatisation de la technique et l’automatisation de la psyché (Picabia, Duchamp).

Le pop art

constitue une seconde lignée qui a placé en son cœur ce qui semblait en

périphérie de l’art, c’est-à-dire les médias de masse et leur production

industrialisée. Le cubisme avait

déjà amorcé cette position. Avec le pop art,

l’arrière-plan de notre

perception

est

toujours déjà

constitué par cette

production à grande échelle qui vient

surdéterminer le cadre

esthétique dans lequel est reçue l’œuvre

d’art.

On peut interpréter

la première lignée comme la jointure

étrange entre l’anthropologique et le technologique parce que ce qu’il y aurait

de plus profond en l’être humain serait un

anonymat

et une forme

d’automatisme qui

auraient quelques

proximités avec le technique. La seconde

lignée

retire à

l’œuvre d’art sa

nature d’événement et d’interruption

(il faudrait voir

la provenance exacte de celle-ci pour

savoir si elle n’a jamais

existée historiquement ou

si elle est une reconstitution

après-coup) au profit d’un

pastiche à la frontière d’une production

quasi-illimité,

celle des médias

industrialisés. L’œuvre d’art se

situerait donc en marge

de

la production des

médias la dépassant toujours quantitativement et

la submergeant à la

manière d’un flux.

Or en observant les

résultats produits par l’imagination artificielle c’est-à-dire par l’usage des

technologies de ladite intelligence

artificielle pour produire des

médias

culturels, on remarque bien

formellement ces deux

composantes. D’un côté, le

pastiche de la

culture de masse qui fait penser esthétiquement

à du pop art. D’un

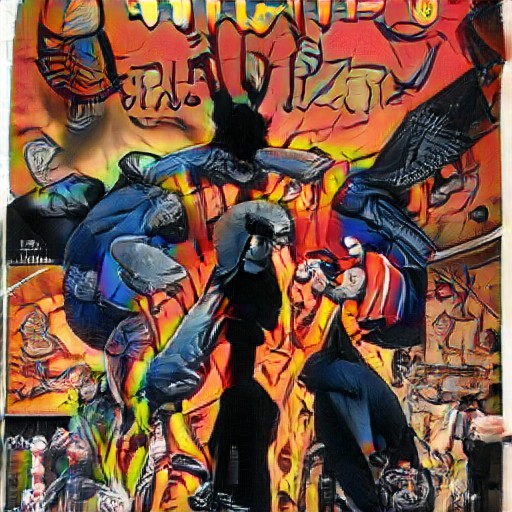

autre côté, un aspect onirique dont la ressemblance visuelle avec le surréalisme

est frappante. Cette double ressemblance s’enracine,

me semble-t-il,

dans la manière

dont ces images sont produites c’est-à-dire dans leur

technogenèse.

Ainsi, les réseaux

récursifs

de neurones

s’alimentent d’un côté de grand

stock d’informations nommé

Dataset dont

certains ont été accumulés grâce à la

participation des internautes depuis l’apparition du

Web

2.0 et qui en ce sens

sont les résultats de la culture de masse. Ils vont opérer sur ces stocks des

calculs statistiques permettant de définir la proximité entre

une

unité et une autre,

par exemple un pixel en

X

et

Y ou une couleur

RGB. Grâce à cette

induction, ils vont pouvoir produire des résultats ressemblants, c’est-à-dire

poursuivre la série pouvant appartenir

au stock. Ainsi ils

vont se placer du côté du pastiche c’est-à-dire d’une référence répétitive. La

répétition est

ici

le but de

l’apprentissage.

Toutefois, pour que cette répétition ne soit pas à l’identique, on introduit du bruit de plusieurs façons. Il peut y avoir du bruit en mélangeant différentes catégories des données, c’est qui permet de créer des formes métamorphiques. Le bruit peut aussi venir d’une accentuation de certains paramètres logiciels pouvant aller jusqu’à la pareidolie. Enfin, il y a un bruit plus classique qui est produit informatiquement pour troubler partiellement la répétition et créer un équilibre entre le reconnaissable et ce qui n’existe pas déjà dans le dataset.

Pour résumer, le pop art

trouve un écho dans le fait que les logiciels d’induction statistique se

nourrissent de données préexistantes et s’alimentent donc de notre société de

production industrielle en tentant de les mimer. Le surréalisme a un écho dans

ces logiciels par l’introduction d’un bruit qui vient brouiller les catégories

et donner un équilibre métastable entre le connu et l’inconnu produisant un

effet Unheimlichkeit car notre système cognitif tente de ramener le second au

premier. Ce double écho n’est pas un lien de causalité historique ou technique,

mais permet d’envisager un contexte culturel dans lequel est baignée notre

appréhension des images. Par ailleurs, une étude cognitive approfondie pourrait

peut être démontrer cet écho est fondé sur des catégories cognitives préalables,

c’est le travail ouvert par Andy Clark dans Surfing Uncertainty : Prediction,

Action, and the Embodied Mind.

La mise en parallèle de la ressemblance de l’imagination artificielle avec certains mouvements des avant-gardes et les modes de fonctionnement technique de ces logiciels permet de tirer la conclusion que la plupart des critiques adressées à l’imagination artificielle sont fondées sur une conception erronée de l’image qui est conçue comment l’apparition une pure singularité sans relation avec un contexte de la culture de masse. Cette conception que l’on retrouve chez Badiou est idéaliste en tant qu’elle est sans rapport avec la production matérielle des images et tire peut-être son origine dans ce moment fort singulier du Romantisme (hypothèse à vérifier Maurice Elie, Lumières, couleurs et nature) lorsque certains écrivains et philosophes ont fait de l’artiste un personnage de fiction, c’est-à-dire une image, leur image.

–

Surrealism constitutes a first lineage of modernity which valued creative power, the unconscious, dreams and states of provoked hallucination, while paradoxically taking an interest in machines and proposing to link the automation of technology and the automation of the psyche (Picabia, Duchamp).

Pop art constitutes a second lineage that placed at its heart what seemed to be on the periphery of art, i.e. the mass media and their industrialized production. Cubism had already initiated this position. With pop art, the background of our perception is always already constituted by this large-scale production, which overdetermines the aesthetic framework in which the work of art is received.

The first lineage can be interpreted as the strange junction between the anthropological and the technological, because the deepest part of the human being is anonymity and a form of automatism that has some proximity to the technical. The second lineage removes from the work of art its nature of event and interruption (one would have to see its exact provenance to know whether it has never existed historically or whether it is an afterthought reconstitution) in favour of a pastiche on the borderline of an almost unlimited production, that of the industrialized media. The work of art would thus be situated on the fringe of media production, always exceeding it quantitatively and overwhelming it like a flow.

However, when observing the results produced by artificial imagination, i.e. by the use of the technologies of the said artificial intelligence to produce cultural media, these two components are clearly visible. On the one hand, the pastiche of mass culture, which aesthetically reminds us of pop art. On the other hand, a dreamlike aspect whose visual resemblance to surrealism is striking. This double resemblance is rooted, it seems to me, in the way these images are produced, that is to say in their technogenesis.

Thus, recursive neural networks feed on one side of a large stock of information called Dataset, some of which has been accumulated thanks to the participation of Internet users since the appearance of Web 2.0 and which in this sense are the results of mass culture. On these stocks they will perform statistical calculations to define the proximity between one unit and another, for example a pixel in X and Y or an RGB colour. Thanks to this induction, they will be able to produce similar results, i.e. to continue the series that may belong to the stock. Thus they will be placed on the side of the pastiche, i.e. of a repetitive reference. The repetition is here the goal of the learning.

However, to ensure that this repetition is not identical, noise is introduced in several ways. Noise can be introduced by mixing different categories of the data, which is what makes it possible to create metamorphic shapes. Noise can also come from an accentuation of certain software parameters that can go as far as pareidolia. Finally, there is a more classical noise that is produced computer generated to partially disturb the repetition and create a balance between the recognizable and what does not already exist in the dataset.

To sum up, pop art finds an echo in the fact that statistical induction software feeds on pre-existing data and therefore feeds on our society of industrial production by trying to mimic them. Surrealism has an echo in these softwares through the introduction of a noise that blurs the categories and gives a metastable balance between the known and the unknown producing a Unheimlichkeit effect as our cognitive system tries to bring the latter back to the former. This double echo is not a historical or technical causal link, but allows us to envisage a cultural context in which our apprehension of images is bathed. Moreover, a thorough cognitive study could perhaps demonstrate that this echo is based on prior cognitive categories, as in the work opened by Andy Clark in Surfing Uncertainty: Prediction, Action, and the Embodied Mind.

By comparing the resemblance of the artificial imagination with certain movements of the avant-gardes and the technical modes of operation of these software programs, it is possible to draw the conclusion that most of the criticisms of the artificial imagination are based on an erroneous conception of the image, which is conceived as the appearance of a pure singularity unrelated to a context of mass culture. This conception found in Badiou’s work is idealistic in so far as it is unrelated to the material production of images and perhaps has its origin in that most singular moment of Romanticism (hypothesis to be verified Maurice Elie, Lumières, couleurs et nature) when certain writers and philosophers made the artist a fictional character, that is to say, an image, their image.