Le pastiche ou la ressemblance de la ressemblance

« Imitation mélangée de la manière et du style de différents maitres. » (Littré)

Les réseaux artificiels de neurones ont comme effet, à partir d’une induction statistique, de sembler produire un résultat familier tout autant que singulier. Le charme du résultat tient en ce qu’il semble avoir une forme connue, inspirée par exemple des portraits picturaux de l’histoire de l’art, et dans le même temps cette forme n’est pas simplement la reproduction à l’identique de ces portraits du passé parce qu’elle est la synthèse de plusieurs de leurs styles rendant alors visible et sensible la synthèse comme telle.

On a souvent critiqué les résultats visuels de ces réseaux parce qu’ils seraient incapables de nouveauté, autre façon du mot d’ordre de l’innovation finalement. Mais c’est là un reproche injuste en un triple sens.

D’une part, la critique se retourne vers l’être humain et présuppose une conception de l’art comme pur évènement et nouveauté. Cette théologie de l’évènement d’inspiration badiousienne (qui est en son fond platonicienne et qui bien que valorisant l’art le fait au titre du refus de la ressemblance et donc de l’imagination productive qui hante la raison), a une longue histoire en particulier dans la littérature et la poésie, elle suppose une anomie radicale de l’œuvre d’art. Mais laquelle d’entre elles est un pur évènement venant disloquer la tradition ? N’est-ce pas plutôt toujours un équilibre fragile entre le passé et ce qui vient qui est en jeu ? Ce pur évènement ne prend-il pas le prétexte de l’art pour élaborer un concept de l’absolu ?

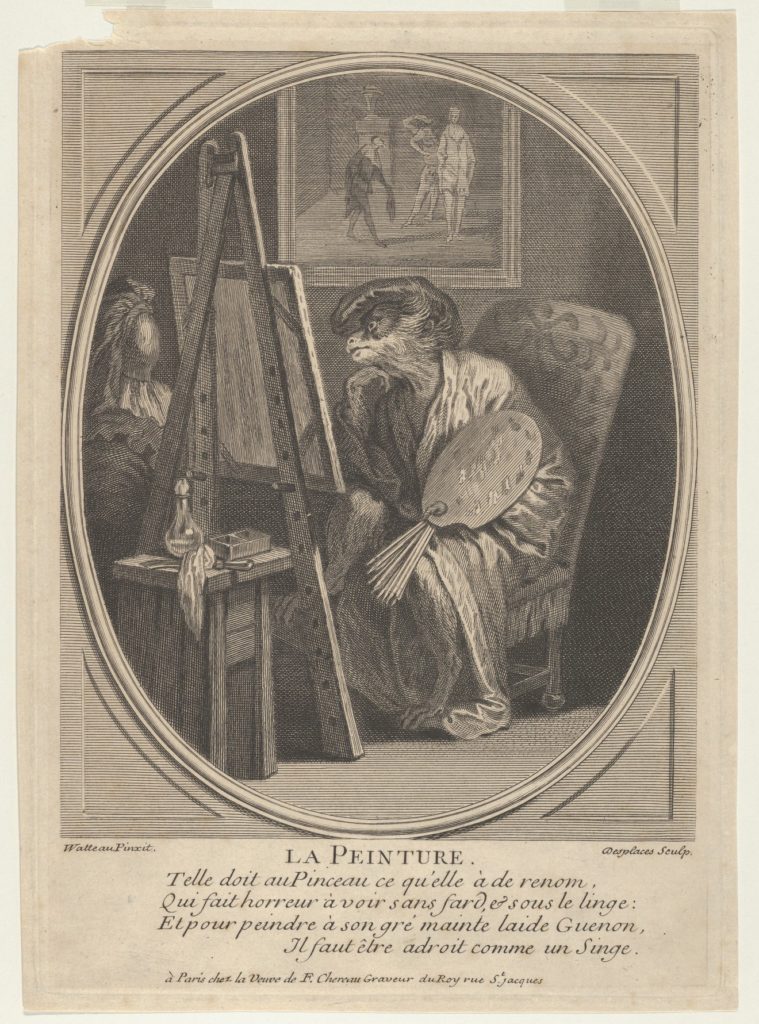

D’autre part, cette critique semble méconnaitre le résultat esthétique des réseaux de neurones qui loin d’être une pure répétition (et on connait bien cette figure et cette tradition de la singerie en art) semble se tenir dans un équilibre instable entre le connu et l’inconnu, selon un certain degré d’imprévisibilité gardant une part de familiarité parce que celui-ci se fonde au moins en partie sur la revisite de la tradition. Que l’induction statistique, avec ses erreurs, puisse précisément créer ce charme singulier de la plasticité devrait moins mener à des critiques présupposant des conceptions erronées en art que d’apporter un éclairage nouveau sur les processus qui étaient à l’œuvre chez les êtres humains au cours de l’histoire de l’art.

Troisièmement, cette critique semble occulter que l’opposition entre tradition et novation n’est pas aussi simple, au moins depuis le postmodernisme (selon l’approche de Lyotard), mais on pourrait, on devrait sans doute remonter aux racines de la modernité picturale pour voir combien dans les Salons, les peintres produisaient du nouveau en reprenant des figures traditionnelles et que c’était précisément cette friction qui choquait. Les nouvelles formes de réalisme pictural ont été ce point de rencontre entre le connu et l’inconnu, et non pas une pure anomie interruptive et un évènement anhistorique.

Comment expliquer l’équilibre parfois charmant des résultats picturaux des réseaux de neurones ? Si l’induction statistique a un fonctionnement relativement simple, elle a des conséquences complexes quand elle entre en résonance avec une tradition culturelle dont sont porteurs les regardeurs humains. Le postmodernisme en tant que reprise différentielle de la tradition prend alors une signification nouvelle dans le contexte de l’automatisation inductive : nous sommes à même de produire une quantité plus importante de médias que les médias servant à alimenter l’apprentissage des machines. Nous produisons par là même une culture de culture et des médias de médias. Il s’agit là de pastiches, mais il faut entendre en ce mot non pas une manière de dévaloriser ces productions, plutôt une façon d’en saisir la spécificité nous faisant voir la synthèse culturelle comme telle.

Cette synthèse culturelle peut s’entendre à plusieurs niveaux : elle est en premier lieu le produit d’une histoire que nous pouvons reconnaitre, deviner, retracer dans les productions logicielles. Elle est en second lieu, l’effort même, la tension de rassembler cette histoire et l’acte synthétique comme telle. Enfin, elle correspond ou répond à la pulsion synthétique des facultés humaines par laquelle nous passons de l’intuition à la raison en passant par l’entendement, en oubliant sans doute au fil de cette route moins rectiligne qu’il n’y parait, le rôle de l’imagination qui infonde la fondation de la synthèse.

C’est en mettant en relation l’histoire, sa synthèse et le synthétique des facultés, que l’induction statistique automatisée ouvre la question transcendantale dans sa réflexivité : son charme si singulier est sans doute un pastiche qui n’est pas sans rapport avec le kitsch, il est en quelque sorte postmoderne, arrivant à ce moment de l’histoire où les hégémonies sont brisées pour laisser peut-être place à une autorité plus hégémonique encore dans le champ politicoéconomique, mais dans le même temps il témoigne de son mouvement même, c’est-à-dire du lien étrange entre la répétition du passé, la production d’une ressemblance culturelle, cet air de famille si troublant des images produites par des réseaux de neurones, et l’advenue objective, au cœur même de cette ressemblance, de quelque chose qui n’existait pas encore. Ajouter au monde des images qui ressemblent à toutes les autres images, c’est ouvrir le possible dont la structure n’est pas d’être une simple rupture, mais une reprise historiale et transcendantale de toutes les autres époques et de toutes les réflexivités passées dont les traces laissées sont les œuvres d’art. La ressemblance de l’image tient dans ses filets le paradoxe de cette répétition de la différence, de ce pastiche de l’histoire qui fait revenir le passé pour la première fois, de ce « revival » généralisé comme ressemblance de la ressemblance. La ressemblance peut être automatisée parce qu’elle est en son fond un automatisme. Percevoir non pas ce qui ressemble (mimétisme naif auquel se soumet la critique anthropomorphique de l’IA), mais la ressemblance comme telle, ce qui fait émerger la ressemblance.

–

Artificial neural networks have the effect, based on statistical induction, of appearing to produce a familiar as well as a singular result. The charm of the result lies in the fact that it seems to have a known form, inspired, for example, by pictorial portraits from the history of art, and at the same time this form is not simply the identical reproduction of these portraits from the past because it is the synthesis of several of their styles making the synthesis as such visible and sensitive.

The visual results of these networks have often been criticized because they are incapable of novelty, another way of saying innovation in the end. But this is an unfair criticism in a threefold sense.

On the one hand, the criticism turns to the human being and presupposes a conception of art as pure event and novelty. This Badian-inspired theology of the event (which is in its essence Platonic and, although it values art as a rejection of resemblance and thus of the productive imagination that haunts reason), has a long history, especially in literature and poetry, and presupposes a radical anomie of the work of art. But which of these is a pure event that dislocates tradition? Isn’t it rather always a fragile balance between the past and what comes next that is at stake? Doesn’t this pure event take the pretext of art to elaborate a concept of the absolute?

On the other hand, this criticism seems to disregard the aesthetic result of neural networks which, far from being pure repetition (and we are well aware of this figure and tradition of the ape in art) seems to stand in an unstable balance between the known and the unknown, according to a certain degree of unpredictability keeping a certain familiarity because it is based at least partly on the revisiting of tradition. That statistical induction, with its errors, can create precisely this singular charm of plasticity should lead less to criticism presupposing erroneous conceptions in art than to shed new light on the processes that were at work in human beings throughout the history of art.

Thirdly, this criticism seems to obscure the fact that the opposition between tradition and novation is not so simple, at least since postmodernism (according to Lyotard’s approach), but one could, one would probably have to go back to the roots of pictorial modernity to see how in the Salons, painters produced something new by taking up traditional figures, and that it was precisely this friction that was shocking. The new forms of pictorial realism were this meeting point between the known and the unknown, and not a pure interruptive anomie and an anhistorical event.

How can we explain the sometimes charming balance of the pictorial results of neural networks? If statistical induction has a relatively simple functioning, it has complex consequences when it resonates with a cultural tradition carried by human viewers. Postmodernism as a differential takeover of tradition then takes on a new meaning in the context of inductive automation: we are able to produce more media than the media used to feed the learning of machines. We thereby produce culture of culture and media of media. These are pastiches, but this is not a way of devaluing these productions, but rather a way of grasping their specificity, making us see the cultural synthesis as such.

This cultural synthesis can be understood on several levels: first of all, it is the product of a history that we can recognize, guess at, and trace in software productions. Secondly, it is the effort itself, the tension of gathering this history and the synthetic act as such. Finally, it corresponds or responds to the synthetic impulse of the human faculties through which we pass from intuition to reason through understanding, forgetting, no doubt, along this road less straight than it seems, the role of imagination which infuses the foundation of synthesis.

This cultural synthesis can be understood on several levels: first of all, it is the product of a history that we can recognize, guess at, and trace in software productions. Secondly, it is the effort itself, the tension of bringing this story together and the synthetic act as such. Finally, it corresponds or responds to the synthetic impulse of the human faculties through which we pass from intuition to reason through understanding, forgetting, no doubt, along this road less straight than it seems, the role of imagination which infuses the foundation of synthesis.

It is by linking history, its synthesis and the synthesis of faculties, that automated statistical induction opens the transcendental question in its reflexivity: its so singular charm is undoubtedly a pastiche that is not unrelated to kitsch, it is in a way postmodern, arriving at that moment in history when hegemonies are broken to perhaps give way to an even more hegemonic authority in the political-economic field, but at the same time it testifies to its very movement, that is to say, to the strange link between the repetition of the past, the production of a cultural resemblance, that family resemblance so disturbing of images produced by neural networks, and the objective coming into being, at the very heart of this resemblance, of something that did not yet exist. To add to the world images that resemble all other images is to open up the possible, the structure of which is not to be a simple rupture, but a historical and transcendental revival of all other eras and all past reflexivities, the traces of which are left by works of art. The resemblance of the image holds in its nets the paradox of this repetition of difference, of this pastiche of history that brings back the past for the first time, of this generalized “revival” as resemblance of resemblance. Resemblance can be automated because it is basically an automatism. Perceiving not what resembles (the naive mimicry to which the anthropomorphic critique of AI submits), but the resemblance as such, which makes the resemblance emerge.