AI narrations and fictions without narration

Artificial intelligence is a superposition of technologies and discourses whose superpositions must be considered. It seems ineffective to deflate the emphasis of speeches by reducing it to an alleged platitude of the reality of technical developments, because this would conceal the fact that these same developments often find their cause in speeches and imaginaries. There is thus a retroactive loop between the material level of technologies and the cognitive level of speech. It is indeed in this in-between that a critical discourse can try to look at this relationship while considering its own conditions of possibility in order not to exclude itself from the reflection.

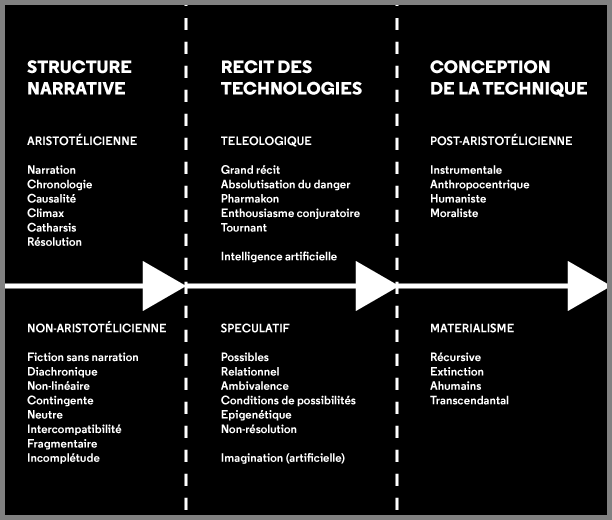

If we consider artificial intelligence from a narrative point of view, we can see that its narrative dates back to the 1950s and 1960s and mixes technological probabilities and science fiction imagination. Between the two, there again a certain feedback feeding on each other in an inextricable loop. The narrative, even beyond its content if we focus only on its structure, seems at least to adopt a classic form since it is a question of extreme danger, to say the least apocalyptic, and a possibility of overpower if we are able to convert the situation.

This narrative structure seems close to the canons defined by Aristotle in his Poetics (chapter 6, even if we should distinguish here the means of action and those of narration). There’s a beginning, an end, an climax. There is danger and cathartic identification. In short, nothing but very classic here. Everything happens as if artificial intelligence were developing the structure of an imaginary already known and which runs through the history of the West and civilizations. Fear of extinction and replacement, death and the possibility of rebirth. The stakes seem immense since it is a question of the very survival of the human species and its nature, i.e. the very conditions that allow a subject to pose the stakes.

I would like to highlight three points. The first is that this narrative, which meets Aristotelian norms, is analogous to an instrumental and anthropological conception of technique, and thus encloses us in another aspect of this philosophy dealing more specifically with the question of technique according to the material, formal, final and efficient quadruple causality. The idea of a conversion of the danger of artificial intelligence into a possible emancipation corresponds exactly to the idea of a technique that could escape our power and that we should bring back to our advantage placing the human being at the centre of its use. There is a causal embeddedness between the narrative structure and the general conception of the technique.

Secondly, the tone of this classic narrative of artificial intelligence is what one could call, taking up a concept by Jacques Derrida, conjurative enthusiasm. The latter makes it possible to define the type of ambivalent affect at stake in this narrative, which consists in increasing the dangers in order to construct the authority of a therapy according to the logic of the pharmacon. Thus, artificial intelligence is conjured as much as it is desired, creating an ambivalence of discourse and an authority that must be deconstructed layer by layer. This conjurative enthusiasm is the dominant emotional tone (Stimmung) on the question of technique.

The third and last point I would like to make here as a possible avenue of work is to point out that if artificial intelligence is considered from a strictly instrumental point of view because of an imaginary developed by a narrative responding to a classical identification structure and thus obliges us to an anthropocentric conception, it might be possible to get out of it by considering this time the artificial imagination (ImA) according to a fiction that would no longer meet the same standards of classical narrative. Not only has contemporary literature critically brought into play the linearity and authority of narrative, that is to say of the narrator, but also if we go back into the history of media arts there was a time when one of the fundamental questions facing artists was that of imagining new modes of fiction.

I would like to highlight three points. The first is that this narrative, which meets Aristotelian norms, is analogous to an instrumental and anthropological conception of technique, and thus encloses us in another aspect of this philosophy dealing more specifically with the question of technique according to the material, formal, final and efficient quadruple causality. The idea of a conversion of the danger of artificial intelligence into a possible emancipation corresponds exactly to the idea of a technique that could escape our power and that we should bring back to our advantage placing the human being at the centre of its use. There is a causal embeddedness between the narrative structure and the general conception of the technique.

Secondly, the tone of this classic narrative of artificial intelligence is what one could call, taking up a concept by Jacques Derrida, conjurative enthusiasm. The latter makes it possible to define the type of ambivalent affect at stake in this narrative, which consists in increasing the dangers in order to construct the authority of a therapy according to the logic of the pharmacon. Thus, artificial intelligence is conjured as much as it is desired, creating an ambivalence of discourse and an authority that must be deconstructed layer by layer. This conjurative enthusiasm is the dominant emotional tone (Stimmung) on the question of technique.

The third and last point I would like to make here as a possible avenue of work is to point out that if artificial intelligence is considered from a strictly instrumental point of view because of an imaginary developed by a narrative responding to a classical identification structure and thus obliges us to an anthropocentric conception, it might be possible to get out of it by considering this time the artificial imagination (ImA) according to a fiction that would no longer meet the same standards of classical narrative. Not only has contemporary literature critically brought into play the linearity and authority of narrative, that is to say of the narrator, but also if we go back into the history of media arts there was a time when one of the fundamental questions facing artists was that of imagining new modes of fiction.

I would like to distinguish here between fiction, which is a regime of the possible, and narrative, which is under the authority of the narrator. In this history of media arts, the potential for alternative narratives that were so important in the 1980s and 1990s seem strangely abandoned today. From the research of Bill Seaman, Jean-Louis Boissier, David Blair, David Rokeby or Geogres Legrady, there are still many others, each in its own way opening up the possibility of a narration-free fiction (FsN) since the authority of the narrator was virtually replaced, according to a degree of intensity varying from one artist to another, by the free interplay of the actor and the non-linearity of the reading medium. Fiction no longer had as its objective to cure the disorder of existence by proposing an ordered and synthetic thread, but to open its contingency. It seems to me that there is still today in this fiction without narration a more contemporary imagination than the return to a storytelling that only generalizes Aristotle in the mass media and in everyday life.

There is here a lost thread of history that we should be able to repeat, we could say darn, in order to develop a conception of technique, that of artificial intelligence, that is no longer only instrumental and simply anthropological. It is also in this sense that artificial imagination should be understood as a higher level of reflexivity in relation to artificial intelligence and a way of transforming the enchantment between the structure of the narrative and the conception of the technique. Imagination is not only a technology, a discourse, but also a methodology that can analyze and deconstruct the intrication of cognitive and technological artificial intelligence. From then on, building fictions without narration also means deconstructing the authority of conjurative enthusiasm and coming out of a simplistic discourse that puts the danger in scene only to gain the authority of a doctor who could cure us or a priest who could save us. There is therefore a political stake in artistically developing a non-aristotelian fiction which would no longer have the aim of bringing technologies into the framework of a pre-existing narrative, but rather of inventing fictions based on the characteristics of the technological medium. Thus to deconstruct AI is to propose an ImA which is at the same time a reflexive method and artistic productions whose model could be rooted in the experience of Immaterials (1985).