La scène des enchères / The Auction Stage

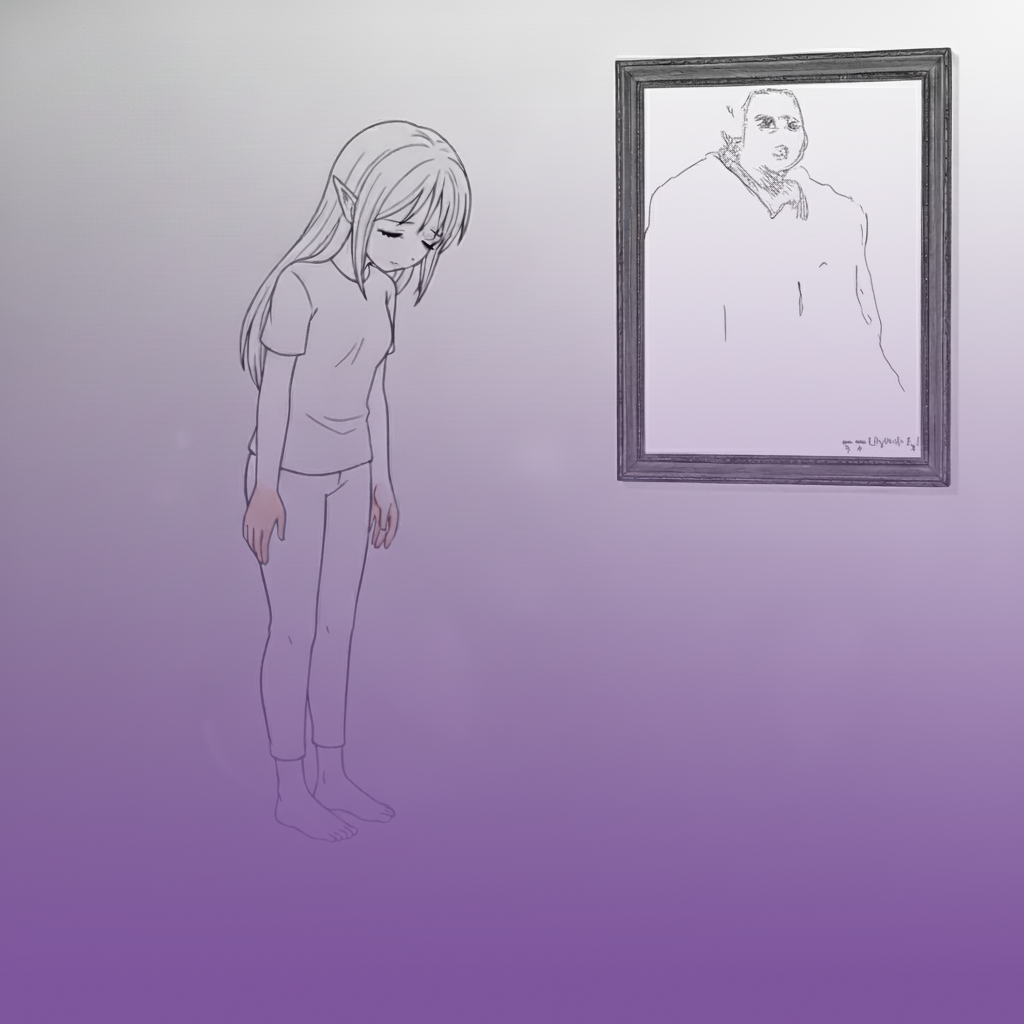

Il existe un étrange phénomène contemporain, une coïncidence troublante entre le moment où certaines pratiques artistiques accèdent à une visibilité médiatique et le moment où ces mêmes pratiques s’inscrivent dans des logiques de circulation économique spectaculaires. Ce n’est pas la qualité esthétique qui détermine l’émergence d’une œuvre dans l’espace public, mais plutôt l’expression d’une puissance, d’une force qui se manifeste par des chiffres, des montants, des records. Cette puissance n’a rien à voir avec l’intensité sensible d’une forme ou avec la pertinence d’une question posée par un travail artistique. Elle relève d’un tout autre régime : celui de la valorisation comme mise en scène, comme théâtralisation d’un pouvoir qui s’auto-institue en se manifestant.

La vente aux enchères constitue un dispositif particulier. Ce n’est pas simplement un lieu d’échange, c’est un espace scénique où se joue une dramaturgie spécifique. Les enchérisseurs ne sont pas de simples acheteurs : ils sont les acteurs d’un rituel où se performe la domination. Chaque surenchère est une déclaration de puissance, chaque montant atteint est une mesure de cette puissance. L’objet qui circule dans ce dispositif devient secondaire, il n’est que le prétexte de cette mise en scène. Ce qui compte, ce n’est pas ce que l’objet dit, propose ou questionne, mais ce qu’il permet de montrer : une capacité à mobiliser du capital, à transformer cette mobilisation en événement, à faire de cet événement une nouvelle qui se propage.

Le discours qui entoure ces transactions adopte systématiquement une rhétorique de l’exceptionnel, du jamais-vu, de la rupture historique. On ne parle pas d’une œuvre, on parle d’un “premier”, d’une “percée”, d’un “tournant”. Cette rhétorique n’est pas descriptive, elle est performative : elle institue l’événement qu’elle prétend simplement rapporter. Le journaliste qui titre sur un montant record ne fait pas œuvre d’information, il participe à la construction d’un mythe, celui d’une valeur qui se révèle, qui émerge soudainement comme une évidence. Mais cette évidence n’a rien d’évident. Elle est le produit d’une machinerie discursive qui transforme un prix en légitimité, une transaction en reconnaissance, un chiffre en qualité.

L’économie est indifférente à son objet. C’est là sa puissance propre : elle peut s’appliquer à n’importe quoi, réduire toute singularité à une équivalence abstraite, traduire toute différence qualitative en différence quantitative. Cette capacité de traduction universelle fait de l’économie un métalangage possible pour parler de tout. On peut parler d’art du point de vue économique comme on peut parler de santé, d’éducation ou de relations humaines du point de vue économique. Ce n’est pas l’objet qui résiste, c’est notre capacité à maintenir d’autres régimes de discours, d’autres modalités d’attention, d’autres critères d’évaluation.

Quand un média parle d’art uniquement parce qu’une vente aux enchères a atteint un certain montant, il ne parle pas d’art. Il parle de circulation du capital, de stratification sociale, de construction de distinctions. L’œuvre elle-même disparaît derrière le montant, elle devient illustration d’une transaction, exemple d’une valorisation. Le contenu de l’œuvre, ce qu’elle propose à voir ou à penser, devient parfaitement accessoire. Ce qui compte, c’est le fait qu’elle ait été évaluée, mesurée, classée selon une échelle qui n’a rien à voir avec ses propriétés sensibles ou conceptuelles.

Cette réduction n’est pas innocente. Elle révèle quelque chose de notre rapport contemporain à l’art, ou plutôt de l’absence de rapport. Car parler d’art à travers le prisme de sa valeur marchande, c’est précisément éviter de parler d’art. C’est se dispenser de regarder, de percevoir, de penser. C’est remplacer l’expérience esthétique par un indicateur chiffré, la confrontation avec une forme par la reconnaissance d’un statut. L’œuvre devient un token, au sens économique : elle circule non pas pour ce qu’elle est, mais pour ce qu’elle représente dans un système d’échanges qui lui est extérieur.

Il serait tentant de dénoncer moralement cette situation, de critiquer la marchandisation de l’art, de pointer du doigt la corruption du jugement esthétique par l’argent. Mais cette critique morale manque l’essentiel. Elle présuppose qu’il existerait un art pur, non contaminé par l’économie, et que la vente aux enchères serait une profanation de cette pureté. Or cette pureté n’a jamais existé. L’art a toujours circulé, été évalué, échangé. Ce qui change, c’est le moment où cette circulation devient le seul discours possible sur l’art, où elle absorbe tous les autres discours, où elle devient l’unique modalité de légitimation.

La critique moraliste de la marchandisation rejoint paradoxalement ce qu’elle croit dénoncer. En réduisant l’œuvre à sa dimension marchande pour mieux la critiquer, elle reproduit exactement l’opération qu’elle prétend combattre : elle ne laisse de place qu’à l’économie. Elle renforce la domination qu’elle veut défaire, elle participe à la saturation de l’espace discursif par la seule question de la valeur marchande. L’œuvre n’existe plus que comme enjeu d’une bataille entre valorisation et dénonciation de cette valorisation, jamais comme expérience sensible ou proposition conceptuelle.

Certains universitaires reprennent ce mot d’ordre sans le questionner. Ils parlent d'”innovation”, de “disruption”, de “percée historique” là où il ne s’agit que de visibilité médiatique générée par une transaction. Cette reprise académique d’un discours économique produit un effet de légitimation particulièrement efficace : elle transforme une valorisation purement économique en reconnaissance esthétique. Le discours universitaire, supposé critique et analytique, devient le vecteur d’une confusion entre deux ordres qui n’ont rien à voir l’un avec l’autre.

Cette confusion n’est possible que parce que l’économie offre un cadre apparemment objectif, des chiffres qui semblent incontestables, une hiérarchie qui paraît évidente. Face à l’incertitude du jugement esthétique, face à la multiplicité des interprétations possibles, face à la fragilité de toute évaluation qualitative, le prix semble offrir une certitude rassurante. Mais cette certitude est illusoire : elle ne dit rien de l’œuvre, elle ne dit quelque chose que du système qui l’a produite.

Parler d’art parce qu’il y a eu une vente aux enchères, c’est donc purement et simplement parler de vente aux enchères. Ce n’est pas parler d’art. C’est substituer à l’expérience esthétique le spectacle de la puissance économique, à l’attention aux formes l’attention aux montants, au questionnement esthétique la célébration d’une domination qui s’auto-institue en se manifestant publiquement. C’est participer à une logique où l’art n’existe plus que comme prétexte à une mise en scène dont il est absent.

There exists a strange contemporary phenomenon, a troubling coincidence between the moment when certain artistic practices gain media visibility and the moment when these same practices become inscribed in spectacular economic circulation logics. It is not aesthetic quality that determines a work’s emergence in the public space, but rather the expression of a power, a force that manifests itself through numbers, amounts, records. This power has nothing to do with the sensible intensity of a form or with the relevance of a question posed by an artistic work. It belongs to an entirely different regime: that of valorization as staging, as theatricalization of a power that institutes itself by manifesting itself.

The auction constitutes a particular apparatus. It is not simply a place of exchange, it is a scenic space where a specific dramaturgy unfolds. Bidders are not mere buyers: they are actors in a ritual where domination is performed. Each bid is a declaration of power, each amount reached is a measure of that power. The object circulating in this apparatus becomes secondary, it is merely the pretext for this staging. What matters is not what the object says, proposes or questions, but what it allows to be shown: a capacity to mobilize capital, to transform this mobilization into an event, to make this event into news that propagates.

The discourse surrounding these transactions systematically adopts a rhetoric of the exceptional, the unprecedented, the historical rupture. One does not speak of a work, one speaks of a “first,” a “breakthrough,” a “turning point.” This rhetoric is not descriptive, it is performative: it institutes the event it claims merely to report. The journalist who headlines a record amount is not doing information work, he participates in the construction of a myth, that of a value that reveals itself, that suddenly emerges as self-evident. But this evidence is not evident at all. It is the product of a discursive machinery that transforms a price into legitimacy, a transaction into recognition, a number into quality.

Economy is indifferent to its object. Therein lies its proper power: it can apply to anything, reduce any singularity to abstract equivalence, translate any qualitative difference into quantitative difference. This capacity for universal translation makes economy a possible metalanguage for speaking about everything. One can speak of art from an economic point of view as one can speak of health, education or human relations from an economic point of view. It is not the object that resists, it is our capacity to maintain other regimes of discourse, other modalities of attention, other evaluation criteria.

When a media outlet speaks of art only because an auction has reached a certain amount, it is not speaking of art. It speaks of capital circulation, social stratification, construction of distinctions. The work itself disappears behind the amount, it becomes illustration of a transaction, example of a valorization. The content of the work, what it proposes to see or think, becomes perfectly accessory. What matters is the fact that it has been evaluated, measured, classified according to a scale that has nothing to do with its sensible or conceptual properties.

This reduction is not innocent. It reveals something about our contemporary relationship to art, or rather about the absence of relationship. For to speak of art through the prism of its market value is precisely to avoid speaking of art. It is to dispense with looking, perceiving, thinking. It is to replace aesthetic experience with a numerical indicator, confrontation with a form with recognition of a status. The work becomes a token, in the economic sense: it circulates not for what it is, but for what it represents in a system of exchanges that is exterior to it.

It would be tempting to morally denounce this situation, to criticize the commodification of art, to point the finger at the corruption of aesthetic judgment by money. But this moral critique misses the essential. It presupposes that there would exist a pure art, uncontaminated by economy, and that the auction would be a profanation of this purity. Yet this purity has never existed. Art has always circulated, been evaluated, exchanged. What changes is the moment when this circulation becomes the only possible discourse on art, when it absorbs all other discourses, when it becomes the unique modality of legitimation.

The moralistic critique of commodification paradoxically joins what it believes it denounces. By reducing the work to its market dimension in order to better criticize it, it reproduces exactly the operation it claims to combat: it leaves room only for economy. It reinforces the domination it wants to undo, it participates in the saturation of the discursive space by the sole question of market value. The work no longer exists except as the stake of a battle between valorization and denunciation of this valorization, never as sensible experience or conceptual proposition.

Some academics take up this watchword without questioning it. They speak of “innovation,” of “disruption,” of “historical breakthrough” where there is only media visibility generated by a transaction. This academic appropriation of an economic discourse produces a particularly effective legitimation effect: it transforms a purely economic valorization into aesthetic recognition. Academic discourse, supposedly critical and analytical, becomes the vector of a confusion between two orders that have nothing to do with one another.

This confusion is only possible because economy offers an apparently objective framework, numbers that seem incontestable, a hierarchy that appears evident. Faced with the uncertainty of aesthetic judgment, faced with the multiplicity of possible interpretations, faced with the fragility of any qualitative evaluation, price seems to offer a reassuring certainty. But this certainty is illusory: it says nothing about the work, it only says something about the system that produced it.

To speak of art because there has been an auction is therefore purely and simply to speak of auction. It is not to speak of art. It is to substitute for aesthetic experience the spectacle of economic power, for attention to forms attention to amounts, for aesthetic questioning the celebration of a domination that institutes itself by manifesting itself publicly. It is to participate in a logic where art no longer exists except as pretext for a staging from which it is absent.